Lampang Airport: Summary thru 1942

Lampang (Google Maps link)1 became the defense center for northwest Thailand probably because it had rail, road, and air transport facilities:

- The Royal Thai Railway had connections direct from the south in Bangkok and its commercial port, Khlong Toei.

- The Phahonyothin Road, the main north-south road in Thailand (now Route 1) continued north from the rail station at Lampang to Mae Sai (Google Maps link) at the border across from Tachileik in Burma: then on to Kengtung (Google Maps link), and westward to Meiktila (Google Maps link) and Mandalay (Google Maps link) on the Irrawaddy River, with rail, road, and air transport connections there: Route map (Google Maps link).

- The Lampang “military landing ground” (Google Maps link) accessed the country’s network of airfields.

The alternate choice would have been Chiang Mai (Google Maps link), which was the actual northern railhead for the railway and which had its own airfield, but lacked a critical existing quality road connection north into Burma. It was also rather more off-center geographically to the other military concentrations in northwest Thailand than was Lampang.

Imperial Japanese Army Air Force (IJAAF) units, early based at Lampang Airfield, flew support for Japan’s successful 1942 invasion of Burma. Thereafter Lampang’s importance declined as Japan’s limited manufacturing base, initially burdened by the IJAAF’s continual combat losses, and later confounded by Allied bombing, produced ever-decreasing new aircraft for Japan’s combat fronts — with reduced numbers finding their way to Thailand, and Lampang.

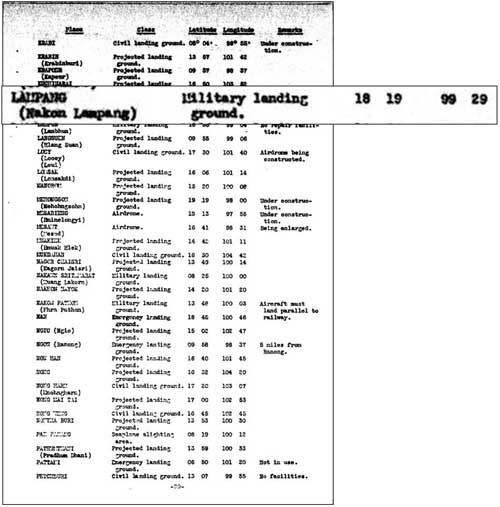

March 1940: Before the war, a US War Department report listed Lampang as a “military landing ground”:2

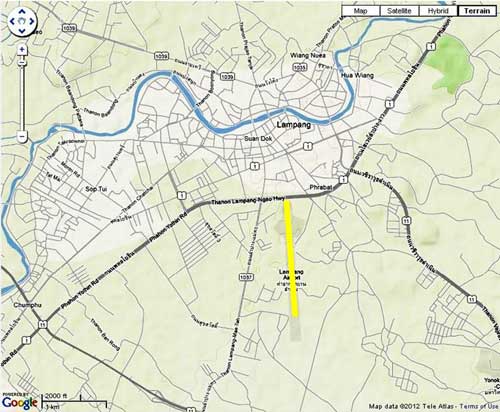

The airfield was “registered” / commissioned on 07 Nov 1923; and an air show touring northern Thailand included Lampang in its itinerary in Feb 1924. Presumably it was at the same general location as the current airport, with photos from the event showing apparent hangars and an extended open area.3 The location specified by the US War Department in 1940 was located south of the City of Lampang at the same site as the current airport (with its runway marked in yellow below):4

An earlier runway’s orientation was approximately perpendicular to the current runway and was referred to in Allied Intelligence reports as the “original” runway.5 The general location of that ENE-WSW runway can be ascertained from sketches in the various Allied intelligence reports which appear in the following chronological history. That orientation is evidenced on-the-ground today primarily by a building similarly aligned to one in a 1944 aerial photo from the Williams-Hunt Collection, plus scattered details barely visible in the latter.

In a Google Earth map of the Lampang airport today is the oddly sited building circled in red:6

A closeup of the building reveals that it is actually two:7

On the ground, it looks like this:8

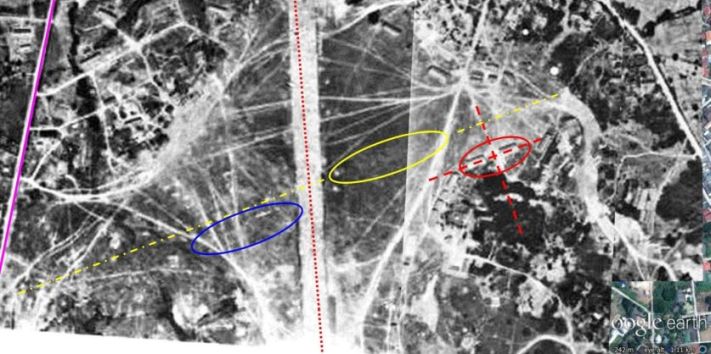

The architectural style appears to be post-war. Curiously, different buildings appeared at the same location with the same alignment with approximately the same exterior dimensions in a 1944 aerial photo of the airfield. The distinguishing difference appears mainly in the middle detail, between the two “sides”:9

. . . as extracted from this photo: 10

Details common to both images are tagged. The purple line on the left traces current Thai Highway No 1037. The current N-S runway center line is shown in dotted red (that it does not match perfectly between the two images may be due to distortions in the photo or perhaps the runway was later slightly realigned). The red‑circled buildings also appear similar in the two images.

The earlier ENE-WSW runway is shown as a yellow center line. Its alignment parallels the building(s). It also parallels some obscure details on the left circled in blue. The yellow circled area denotes a long section of slightly different ground texture which is assumed to be a vestige of the old runway.

The heading of that earlier runway scales as 070°/250° (07/25). Such an orientation is unusual since runways are usually aligned to take advantage of prevailing winds in the region, which have been out of the north in recent history. In fact, those winds justify the approximate north-south orientation of the current runway. When the old runway was abandoned is unclear. While that earlier runway is referred to as the “original”, the Lampang airstrip was once merely a large circular grassy area on which aircraft could land into whatever direction the wind was blowing.11

1941: Lampang was not included in airmail routes in northwest Thailand in 194112 (See description of air mail service, “Aerial Transport Co,” below in March 1942):

That Lampang had not been included in the airmail system might have been the result of its proximity to the Chiang Mai railhead, just 109 km northwest by rail.13 Chiang Mai was also nearer to the western border towns of Mae Hong Son and Mae Sariang, which were of particular concern to the Thai government because they were among the most remote areas of the country and comparatively lawless (even into the 1970s).14

26-27 October 1941: Japanese aircraft, Ki-15s (offsite link), were observed flying over the RAF airfield, Kyedaw (now Kaytumati, Google Maps link), at Toungoo, Burma, at high altitude, obviously doing reconnaissance. Flying out of Gia Lam Airfield (Google Maps link) in Hanoi, the flight path of the planes might have rendered them visible in various parts of Northern Thailand, including Lampang. Indeed, such aircraft might also have been observing various points throughout Thailand, including Lampang.15

07 December 1941: A US Army Air Corps report, Airports in the Far East, probably conveniently redated to 07 December 1941, provided this information about the Lampang air facility:16

TRANSCRIPT:

| LAMPANG / Lampang (P9-18) | |

| 18 19 N / 99 29 E17 | |

| No information | |

| 3 mi [5 km] from town | |

| 4920 x 810018 | |

| Grass | |

| 2 hangars; wind cone |

12 December 1941: Darrell Berrigan, an adventurous and prolific United Press reporter, fleeing north from Bangkok through Lampang and Mae Sai into British Burma, recorded on this date of learning that the ‘Lampang Airdrome’ had just been occupied by IJA troops.19

Date uncertain, but about the same time, Christian missionaries from Chiang Mai, Nan (Google Maps link), and Phrae (Google Maps link) traveled to Lampang from where they were bussed north to Mae Sai and crossed into Burma.20

22 December 1941: Local Chiang Mai photographer / historian Boonserm Satrabhaya recalled in his popular history of air activities around Chiang Mai:

When Field Marshal Phibun stationed army troops in the north at the beginning of the Great South East Asia War with Major General Jaroon Seri-reng-rit as northern commander-in-chief, the Royal Thai Air Force established a large air base at Lampang with Air Vice-Marshal Feun Ritakani as division commander coordinating with the army [which was also present].21

Royal Thai Air Force (RTAF) history records:

Wing (Kong Bin Noi Phasom) 80 relocated [from Ko Kha] (Google Maps link) to Lampang, with foong bins (squadrons) gathered from other units:22

-

- 22 (observation) from Chantaburi (Google maps link): 9 US-sourced Vought Corsair RTAF Attack Aircraft Type 1, acquired in 1934

- 32 (attack) from Nakhon Ratchasima (Korat) (Google maps link): 9 US-sourced Curtiss Hawk II RTAF Fighter Aircraft Type 9, acquired in 1934

- 41 (fighter) from Chantaburi: 10 US-sourced Curtiss Hawk III RTAF Fighter Aircraft Type 10, acquired in 1935

23 December 1941: The IJAAF first attacked Rangoon with units from Bangkok, Rahaeng, and Phnom Penh. Units at Lampang were not involved.23

27 December 1941: Five days later, the RTAF’s 22nd and 41st moved farther north to Chiang Rai (Google Maps link) leaving the 32nd at Lampang.24

29 December 1941: IJAAF 77th Sentai (77th FR (Flying Regiment), a fighter group)25 composed of 30 Ki-27 (offsite link) fighter aircraft (Allied nickname “Nate”) under Lt Col Yoshioka26 relocated from Rahaeng (Tak) (old runway, now obscured by subsequent development; Google Maps link) to Lampang.

IJAAF 10th Hikodan (area air force) under General Hirota Utaka was reassigned from Bangkok to Lampang.27

1942: Local Chiang Mai photographer / historian Boonserm Satrabhaya further recalled:

. . . the Royal Thai Air Force sent [Curtiss] Hawk IIIs (offsite link) to serve in every airport near the northern border, including Lampang . . . . 28

With regard to the Curtiss Hawk IIIs:

RTAF history agreed that the 41st Fighter Squadron with ten Curtiss Hawk IIIs was relocated to Lampang on 22 December 1941, but five days later the unit with its Hawk IIIs moved on to Chiang Rai.

However, the 32nd Attack Squadron with nine US-sourced Curtiss Hawk IIs (offsite link), also assigned there on 22 December continued at that location until 18 February 1942 when it moved to Chiang Mai.29

Both Hawk IIs and IIIs were vintage biplanes.

Boonserm further recalled:

The Japanese brought . . . more than fifty Ki-21, (offsite link) [Type 97 heavy twin-engine bombers, codenamed “Sally”] to their base in Lampang.30

In early 1942, Lampang airfield was also heavily populated with Japanese-manufactured, light and heavy bombers. Young recorded that the 31st Sentai with 25 Ki-30 (offsite link) “Anne” Type 97 light single-engine bombers and RTAF Squadrons 11 and 12 with 11 Ki-30s light bombers each relocated to Lampang in late January-early February 1942. Thus IJAAF and RTAF Ki‑30s gathered at Lampang totalled 47. Nine Japanese Ki-21 (offsite link) “Sally” or “Gwen” Type 97 heavy bombers from RTAF Squadron 62 were located at Lampang during the same period.31

03 January 1942: IJAAF 77th Sentai in its first operation from Lampang dispatched nine Ki-27s which took on fuel at Rahaeng (Tak, from where the unit had relocated), and then strafed the RAF Moulmein Airfield (Google Maps link to modern-day Mawlamyine) destroying four aircraft of the Indian Air Force’s 4 Coast Defence Flight. Many more flights originated from Lampang during the month.32

10 January 1942: In the two week period, 28 December 1941 – 10 January 1942, the Lampang-based IJAAF 77th Sentai lost ten Ki‑27s, almost one-third of its aircraft complement.33

20 January 1942: IJAAF 77th Sentai participated in the IJA’s invasion of Burma from Mae Sot (Google Maps link) towards Moulmein, providing escort for light bombers which were, in turn, supporting ground troops, and strafed the RAF airstrip at Moulmein.34

22 January 1942: By this date, the IJAAF 10th Hikodan (area air force) in Lampang had added the 70th Independent Chutai (squadron), composed of four Ki-15 “Bab” Type 97 command reconnaissance aircraft.35

The 77th Sentai was recorded as having 25 Ki-27s (11 short of its complement).36

Late January – early February 1942: RTAF’s Kong Bin Yai Phasom Phak Phayap (Northwestern Combined Group) moved north from Don Muang near Bangkok. One of its combined wings, Kong Bin Noi Phasom 85, went to Lampang with Squadrons 11 and 12, each with 11 Japanese-made Ki-30 “Ann” Type 97 light bombers.37

RTAF Squadron 16, with nine US-manufactured Curtiss Hawk 75Ns (offsite link),38 was reassigned from Don Muang to Wing 85 to provide escort for those RTAF Ki-30s; late in the month, Squadron 16 received twelve new Japanese Ki-27 “Nate” Type 97 fighters.

RTAF Squadron 62, with nine Japanese Ki-21 “Sally” Type 97 heavy bombers moved from Lopburi to Lampang.39

06 February 1942: RTAF light bomber Squadrons 11 and 12 (Ki-30s), escorted by Squadron 16 (Hawk 75Ns) attacked Chinese Nationalist positions near Loi Moei, ดอยเหมย (Google Maps link), a few km southeast of Kengtung on Burma Route 4 per map p 302. All three RTAF units were based at Lampang.40

06-17 February 1942: RTAF’s Kong Bin Yai Phasom Phak Phayap (Northwestern Combined Group), at Lampang, in support of the advance of Thai Army ground troops, bombed a Nationalist Chinese 93th Division installation at Loi Moei where 11,000 troops were based.41

10-20 February 1942: IJAAF 31st Sentai with 25 Ki-30 “Anne” Type 97 light bombers moved from Phitsanulok (Google Maps link) to Lampang.42

19 February-15 March 1942: RTAF Squadron 16, flying out of Lampang, patrolled daily over Chiang Mai and Chiang Rai.43

23 February 1942: By this date, IJAAF 77th Sentai had lost 15 Ki-27s. Two days later, the 77th was reported as having 23 aircraft (13 short).34 A few days later, the number available had risen to 25 (11 short).44

26 February 1942: Some (most?) Ki-27s of IJAAF 77th Sentai were relocated from Lampang to Mudon (Google Maps link), Burma. The sentai had arrived in Lampang from Rahaeng only on 29 December 1941.45

28 February 1942: IJAAF 10th Hikodan headquarters, which had been assigned to Lampang from Bangkok on 29 December 1941, moved from Lampang to Mudon, Burma.45

The 77th Sentai reported 14 Ki-27 fighter aircraft available (ie, 16 short). The number just in Lampang was not published.46

March 1942: Thailand’s airmail service had begun in 1922, provided by the RTAF.47 Thailand’s commercial air service, The Aerial Transport Company, had taken over responsibility for scheduled mail and transport service in 1931.48 Coverage had expanded by the end of 1941 as noted. By March 1942, however, that service had been sufficiently compromised by shortages that the RTAF began its own mail service with Fairchild 24Js (offsite link) and Rearwin 8500 Sportsters (offsite link) aircraft. The commercial service had never included Lampang in its airmail network, possibly because the air facility had been classified as a “military landing ground”; hence airmail service for that location would have always been a responsibility of the RTAF.49

07-08 March 1942: IJAAF 77th Sentai Ki-27 fighter aircraft still located at Lampang were grounded due to fog and unable to provide support in the final IJA attacks on Rangoon.46

18 March 1942: Four Ki-15s IJAAF from 70th Independent Squadron had arrived in Lampang on 22 January 1942; two Ki-15s were lost before the unit’s relocation to Moulmein on this date: one more was subsequently destroyed on the ground. The last aircraft eventually moved to Bangkok.50

20 March 1942: The IJAAF Order of Battle, Burma Theater of Operations, for this date located only two units in Lampang:

- 12th Sentai:

- 31 Ki-21-II “Sally” Type 97 heavy bombers

- 51st Independent Chutai with two different command reconnaissance designated aircraft:

22 March 1942: British intelligence reported that Lampang was being improved for use as a military airbase.52 The comment suggests a lack of sharing of information among the Allies at this early date in the South East Asian Theatre: the US had classified the Lampang airstrip as a “military landing ground” a year before in a US War Department publication (dated 15 March 1941).

24 March 1942: On 24 March 1942, Flying Tiger Squadron Leader Jack Newkirk on a flight to attack enemy facilities in Lampang, apparently confused Lampang with Lamphun and never reached Lampang. He fatally crashed near Lamphun.53

13-26 April 1942: RTAF light bomber Squadrons 11 and 12, based at Lampang, bombed Nationalist Chinese 93rd Division elements at Loi Moei and Mong Hpayak (Google Maps link).54

05-09 May 1942: RTAF Squadron 62, with nine Japanese Ki-21 “Sally” Type 97 heavy bombers hit Kengtung (Google Maps link) and Mongyawng (Google Maps link) in support of Thai ground forces.55

17-27 May 1942: RTAF Squadrons 11 and 12 and six Ki-21 “Sally” heavy bombers from Squadron 62, based at Lampang, again bombed Nationalist Chinese 93rd Division elements at Loi Moei. This effort finally allowed the Thai Army to occupy Kengtung.56

31 May 1942: The Royal Thai Army (RTA) headquarters relocated from Lampang to a tobacco factory along the Kok River in Chiang Rai.57

June 1942: Those portions of IJAAF 77th Sentai still at Lampang returned to Lungchen, Manchuria, from which the unit had arrived on 29 December 1941.58

22 June 1942: RTAF light bomber Squadrons 11 and 12 bombed Chieng Rung (Google Maps link to modern-day Jinghong), a supply point in China.59

19-28 June 1942: RTAF light bomber Squadrons 11 and 12 flew out of Lampang to bomb Mong Ma (Google Maps link: not shown by Google Maps, but on the Mong La Road between the “shopping cart” to the north and “Wan Nampyen” to the south).60

July-December 1942: RTAF light bomber Squadrons 11 and 12 made reconnaissance flights along the border and into China’s Yunnan Province. Border patrol work was shared with heavy bomber (Ki-21) Squadron 62.61

October-November 1942: RTAF heavy bomber Squadron 61 with nine Ki-21 bombers transported food from the north of Thailand to Don Muang Airport which, along with Bangkok and Thonburi, were reeling from flooding up to one meter deep.62

December 1942: Mail routes included, connecting to the south from Lampang to Phrae, Phitsanulok, and Bangkok, and to the north from Lampang, Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai, and Kengtung.

The RTAF specified an airmail route which (finally) formally connected Lampang with points south: it ran from Bangkok through Phitsanulok and Phrae and was serviced by Fairchild 24Js.63

In addition, Lampang was the southern terminus for air service linking Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai, and Kengtung (Burma), which was flown by Vought Corsairs (offside link).64

Next: Lampang Airport: 1943

| 2012 Sep 25 | First published on Internet | |

| 2013 Nov 15 | Minor changes; maps realigned to north up; transcripts added. | |

| 2014 Jan 05 | Typos, bad refs, misspellings, etc, hopefully all corrected. Summary added. | |

| 2024 Feb 29 | Converted to WordPress by Ally Taylor | |

| 2025 Oct 16 | Updated, author errors & typos corrected | |

Last Updated on 20 February 2026

- Lampang: the spelling of this transliteration is used throughout almost all references found. The name of the town has evolved over time from Lakhon (not to be confused with Lakon, aka Nakhon Sri Tammarat, south of the Isthmus of Kra), per Graham, WA, Siam: A Handbook of Practical, Commercial, and Political Information (London: Moring, 1913). To confuse matters, Wikipedia‘s article, Lampang (offsite link), lists previous names as Wiang Lakon and Khelang Nakhon. Further confusing is the name of the next major town to the northwest and connected by rail, Lamphun (Google Maps link). To Western eyes and ears, the similarity of the two names, both starting with L, can be frustrating. In the case of Jack Newkirk, ace Flying Tiger pilot, it may have contributed to his early death: with orders to attack Lampang in late March 1942, he inadvertently attacked Lamphun where he fatally crashed.[↩]

- A Survey of Thailand (Siam), (Washington: US War Department, March 15, 1941), Appendix I – Airdromes, Landing Grounds, and Seaplane facilities of Thailand, v. Additional Airdromes, Landing Grounds and Seaplane Facilities of Thailand, “correct up to April 1940”, p 89 (USAF Archive Microfilm Reel B1750 p1811).[↩]

- Photos credited to Edward M Young in ศักดิ์พินิต พรัอมเทพ, ประวัติกองทัพอากาศในช่วงกำเนิดกองทัพอากาศ : ระหว่าง พ.ศ.๒๔๕๓-๒๔๖๐ (กรุงเทพฯ : กรมสารขรรณทหารอากาศ กองทัพอากาศ, ๒๕๖๕), (Air Chief Marshall Sakpinit Promthep, Origins of the Air Force between 1910 and 1937 (Bangkok: Air Force Secretariat, Royal Thai Air Force, 2002) ), pp 221-229[↩]

- Terrain map from Nations Online Project: Searchable Map and Satellite View of Thailand using Google Earth Data (website no longer available). The yellow line marks the approximate 1800 m runway length that Allied intelligence reported in Oct 1943 for the Lampang Aerodrome N-S runway. Annotation by author using Microsoft Publisher.[↩]

- Airfield Report No. 21, Apr 1944, unnumbered page (USAF archive microfilm reel A8055, p 0669) remarks that the “original ENE-WSW runway had been abandoned.[↩]

- Google Earth view of N18°16.629′ E99°30.341 Annotations by author using Microsoft Publisher. [↩]

- ibid, extract[↩]

- Extracts of DSCFs 2211, 2213, & 2215 of 01 May 2014 stitched into a panorama with Microsoft Ice. Photo added to webpage 05 May 2014.[↩]

- Extracts from: 02541.jpg+02548.jpg (next) [↩]

- Extracts from: 02541.jpg+02548.jpg • Williams-Hunt Aerial Photos Collection • Original from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London • Digital Data from Center for Southeast Asia Studies (CSEAS), Kyoto University • Digital Archive from Chulachomklao Royal Military Academy (CRMA), Thailand[↩]

- An earlier runway bearing was previously incorrectly stated as “170°/250°” (17/25) [my mistake]; corrected 05 May 2014. The earliest airfield configurations were almost always circular, per Wikipedia: Aerodromes (offsite link).[↩]

- The map below is a composite of information from Young, Edward, Aerial Nationalism (Washington: Smithsonian Institute, 1995), p ix, and A Survey of Thailand (Siam), (Washington: US War Department, March 15, 1941), p 101, “Civil Air Routes (Jan 1940)”, (USAF Archive Reel A2874, p 1467), superimposed on a “Terrain” map from Nations Online Project: Searchable Map and Satellite View of Thailand using Google Earth Data (website no longer active). Annotations by author using Microsoft Publisher include solid white lines per Young and US War Department, but with dotted lines only per US War Department.[↩]

- Whyte, BR, The Railway Atlas of Thailand, Laos and Cambodia (Bangkok: White Lotus, 2010), pp 28-29.[↩]

- 戦没者遺骨収集の記録 ピルマ・インド・タイ [Journal on Collection of War Dead: Burma, India, Thailand] (Tokyo: All Burma Comrades Organization, 1980), p 452.[↩]

- Ford, Daniel, Flying Tigers (Washington: Smithsonian Books, 2007) p 77.[↩]

- US Army Air Corps, Airports in the Far East (Washington: Intelligence Division, Office of he Chief of the Air Corps, 07 Dec 1941), p 69 (USAF Archive microfilm roll A1285 p 0073). Significance of “(P9-18)” under column heading, Name, is not known.[↩]

- Difference with later data reflects lesser accuracy available in 1941, plus use of the Indian-Thailand Datum (current datum is WGS84).[↩]

- These dimensions apparently refer to a period when air facilities were simply open ground allowing aircraft to take off and land in any direction. See Wikipedia’s Aerodromes (offsite link).[↩]

- From the Sheboygan (Wis) Press, Thu 18 Dec 1941, p 12: “We left on the morning of Dec 11 [from Lampang]. The sealing of the frontier cut off escape for more than 60 Americans and 200 Britons left in Thailand. The next morning [12 Dec] Japanese troops were reported to have occupied the Lamping [sic] airdrome, blocking the northern route to Burma.”[↩]

- Kneedler, William Harding, MD, Refugeeing from Thailand in World War II, unpublished manuscript dated 1943, located in Prince Royal’s College Archives, Chiang Mai.[↩]

- Translation from บุญเสิม สาตราภัย, เชียงใหม่กับภัยทางอากาศ (กรุงเทพฯ: วิญฌูชน, 2003) (Boonserm Satrabhaya, Chiang Mai and the Air War (Bangkok: Winyuchon, 2003) [hereafter Boonserm], p 53 (translated by Wiyada Kantarod). Note that Boonserm was less concerned about getting every detail perfect and very much more concerned about trying to encourage an interest by a Chiang Mai citizenry which seemed generally indifferent about local history.[↩]

- Translation from บระวัติกองทัพอากาศไทย พ.ศ.๒๔๕๖ ๒๕๒๖กองทัพอากาศ พุทธศักราช ๒๕๒๖, Royal Thai Air Force Official History 1913-1983 (Bangkok: Royal Thai Air Force, 1983) [hereafter, RTAF 1913-1983], p 277.

Functions and aircraft ids are from Young, ibid, pp 184‑185 with “types” defined on pp 261-262. Young records a far more complex process involving a comprehensive reorganization of the RTAF with reassignment of units to different commands and relocation of several commands to the far north of Thailand (pp 184-185). He also gives origins other than Ko Kha from which the squadrons were relocated:

22: Chantaburi (Noen Ploi Waen, Google Maps link)

32: Isan (Udon and Korat) (Google Maps links)

41: Lopburi (Khok Kathiam, Google Maps link)J-aircraft listings (offsite link) differ on two out of three units from the other sources. The units it lists were all originally located at Lopburi (per Young):

21: 9 Corsairs

41: 10 Hawk IIIs

62: 9 Ki-21[↩] - Ford, ibid, p 112[↩]

- RTAF 1913-1983, ibid.[↩]

- The source for most of the details in the following was from Dan Ford’s account in The January Air Battle for Rangoon (offsite link). See also an excellent review of 77th Sentai action during this period in Richard Dunn’s The Campaigns of the 77th Hiko Sentai (part 1) and (part 2) (offsite links).

Thai military activities are presented in rather greater detail here because there are so few in-depth sources published in English.[↩]

- Dan Ford’s “Order of Battle 23 Dec 1941: 3rd Hikoshidan, 10th Hikodan”, source no longer on-line, apparently quotes the 30 count from an order of battle dated 23 Dec 1941 presented in Japan’s official military history, Senshi Sosho. However, on 04 Jan 1942, Ford records that the 77th sent out 31 Ki-27s to attack Rangoon. The 31 count, rather than the 30, is consistent with Ford’s tally of losses between 23 – 27 Dec 1941: 1 loss on the 23rd and 4 on the 25th total 5. Subtracted from the original 36 leaves 31.

Richard Dunn in [The Campaigns of the 77th Hiko Sentai] (part 1) (offsite link) records “about 30 [IJAAF] operational fighters” in all of Thailand at first, all from the 77th Sentai.[↩]

- Dan Ford, The January Air Battle for Rangoon (offsite link).[↩]

- Boonserm, ibid, p 56.[↩]

- RTAF 1913-1983, pp 279, 309.[↩]

- Boonserm, ibid p 69.[↩]

- Young, ibid, pp 186[↩]

- Dan Ford’s The January Air Battle for Rangoon (offsite link) plus Richard Dunn provide a fairly detailed descriptions of air activities during this period.[↩]

- Dan Ford’s The January Air Battle for Rangoon (offsite link) along with his offsite webpage that follows, Putting the pressure on Mingaladon; also Bloody Shambles I, p 253 ff.[↩]

- Dan Ford’s Numbers are not important (offline link) [↩][↩]

- Alford, Bob, Lampang Thailand, WWII, unpublished manuscript. [added 15 Sep 2014][↩]

- Shores, Bloody Shambles 1, p 260. [↩]

- Additional background available at Dan Ford’s January 26-29: furballs over Mingaladon (offsite link) [↩]

- Curtiss Hawk 75N: Simplified version for Siam (Thailand) with non-retractable landing gear and wheel pants (per Wikipedia). Young also describes their acquisition in detail: ibid, pp 130-131.[↩]

- Young, pp 184‑187. Clarification: in Jan 1942, the RTAF had a Squadron (Foong Bin) 62 with nine Ki-21 heavy bombers in Lampang (ibid); and the IJAAF had a Wing (Sentai) 62 with fifteen Ki-21 heavy bombers in Bangkok. (Ford, ibid). The potential for confusion went further: the RTAF designation for the Ki-21 was Type 61. RTAF Squadron 62 had a sister squadron, 61, but it flew Martin bombers out of Phrae during this period.[↩]

- Young, p 185.[↩]

- RTAF 1913-1983, p 308[↩]

- Shores, Bloody Shambles II, p 268.[↩]

- Young, p 188.[↩]

- Dan Ford’s Putting the squeeze on Rangoon (offsite link).[↩]

- Dan Ford, ibid.[↩][↩]

- “A new base at Magwe”, Ford, ibid.[↩][↩]

- Young, ibid, p 32.[↩]

- “commercial”: nominally so: it was 51% government-owned. ibid, p 76. Formal title: The Aerial Transport Co of Siam, Ltd, ibid, p 76. 1931: ibid, p 82.[↩]

- ibid, pp 215-216. Aircraft identification: ibid, pp 134, 262.[↩]

- Dan Ford, South Burma falls to the Japanese (offsite link).

Alford, ibid, p 2: one aircraft and crew lost near Chiang Mai 21 Jan 1942; another lost near Sittang River 23 Feb 1942. [added 15 Sep 2014] [↩]

- Bloody Shambles II, p 347. Neither dates of arrival at Lampang (and origin) nor dates for departure (and destination) for these units are available.[↩]

- Dan Ford, Flying Tigers, ibid, p 241.[↩]

- See discussion and references at Wat Phra Yuen.[↩]

- RTAF 1913-1983, p 316. Mong Hpayak: N20°42.4 E100°05.8. Young lists only 13 Apr for this action, but includes Squadron 16 as escort, p 189.[↩]

- Kengtung (principal town for Shan State (East): N21°17.5 E100°36.5 Mongyawng (easterly-most township of Burma): N21°30 E100°55. Young named Mongyawng, not to be confused with the phonetically similar Mongyang (Google Maps link), 100 km NNW of Mongyawng, where vestiges of an airstrip remain (Young, ibid, p 190).[↩]

- RTAF 1913-1983, p 322.[↩]

- Across the Lwoi River (offsite link) in Klykoom’s Thailand and the Second World War (website discontinued when Geocities disbanded, but archived as linked). Where the headquarters had been located in Lampang is not clear — but presumably in the airfield area — nor where the tobacco factory was in Chiang Rai. Info needs verification.[↩]

- Richard Dunn: The Campaigns of the 77th Hiko Sentai (part 2) (offsite link) [↩]

- Young, p 193. Young names Chieng Bung; however, I could find no Chieng Bung. There is a Chieng Rung, with present-day name, Jinghong, the capital of Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan, China, and a likely major supply point in China. It was the historic capital of the former Tai kingdom of Sipsongpanna. The location appears to have been labeled Che-li-hsien on Survey of India map 102C, “Mong Yawng”, dated 1900.[↩]

- ibid, p 192-3.[↩]

- ibid. Young identified activities in this period, 11-12 Jan 1943, targeting only Mong Yang and Mong Hai; and 12 Jan 1943, targeting only Chieng Rung, p 194.[↩]

- Young, ibid, p 195; RTAF 1913-1983, p 325, recorded only Squadron 62 stationed at Phrae as having participated in the emergency airlift.[↩]

- Young, ibid, p 216.[↩]

- ibid. See photo of RTAF Vought Corsair V-93S (offsite link) and Description.[↩]