Appendices

Appendix A. Vought Corsair V-93S Image (offsite link)

Description

This information appears on a Google archive page only: its continued availability is unclear, so the text is reprinted below (and polished):

บ.จ๑ BJ.1 Vought V-93SA Corsair

บ.ฝ๕ BF-5 Vought V-93S Corsair

History

On 30 March 1934, the first 12 Vought Corsairs were delivered from the USA. The initial 12 planes cost $240,156 plus an additional $9,900 covering licensing costs. Nine V-93S and three V-93SA were handed over to the RTAF. The Corsair was called BJ.1 (Attack Type No. 1) or Type 23 in the service of the RTAF. Thailand manufactured locally the V-93S and SA from 1936 on: in 1936 a first batch of 25 planes and in 1937 again 25. In 1940 the last batch of 50 planes were constructed by the Aeronautical Department at Bangsue. The exact number of V-93S in Thai service is not known, but it is believed that there were no less than 130. This means that after 1940 there were additional Corsairs produced to compensate losses.

A trainer version with a P&W Hornet L-975 E3 engine was also built by Thailand. Ten planes were built locally by the Aeronautical Department and designated as BF.5 (Trainer Type No. 5) or Type 87. A special version with a Piston Star R-1820 F-53 engine of 345 hp was also built. It is the same engine as that of the Hawk III, with a three blade propeller. Only three were built or rebuilt.

During WWII, many Corsairs were sent to Chiang Rai and Chiang Tung (in the Shan States in Burma; today called Kengtung). Most of them were destroyed by enemy fire but those surviving in Chiang Tung were burnt by Thai personnel when there was no one left to fly them back to Thailand. The last Corsairs were withdrawn from RTAF service in 1950.

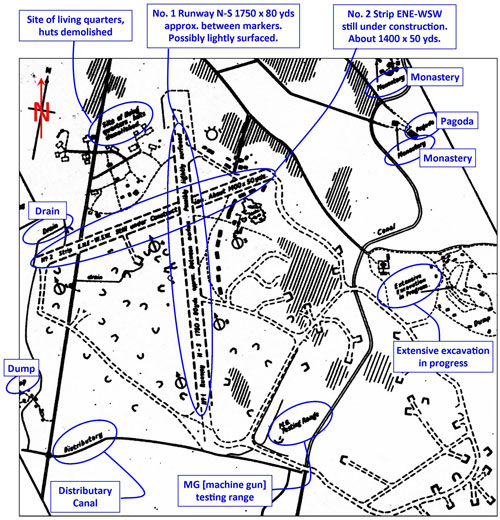

Appendix B. Notes on symbols used in USAAF airfield sketches:

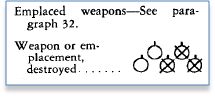

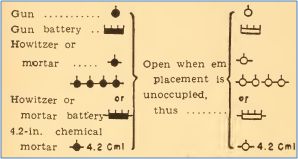

Weapons emplacements:1

Symbol is “open” when emplacement is unoccupied:2

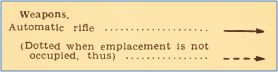

Automatic rifle (assumed superimposed on circle indicating “emplacement”). Dashed line is here not used because it is assumed that empty circle already signifies emplacement is unoccupied:3

And note that the automatic rifle emplacements appear to be numbered, with the highest number, 9. Since numbers are missing in the sequence, it might be assumed that there emplacements outside the coverage of the map sketch.

Antiaircraft weaponry:

Machine gun:4

and5

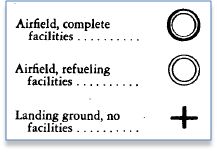

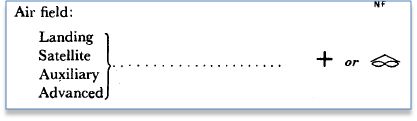

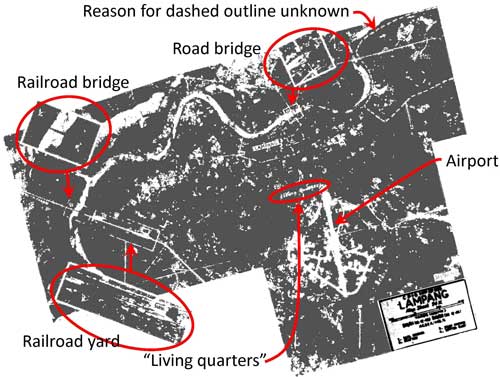

Air fields . . .

Classifications:6

Note that “landing grounds” here means an airfield without “facilities”. Conversely, in an “airport” context, a cross is also defined and perhaps consistently, as:7

But then more ambiguously, under “Military Activities”:8

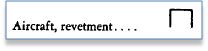

Shelters:6

C. Refugeeing from Thailand in World War II9

by William Harding Kneedler, MD

Transmittal, handwritten on stationery headed:

W Harding Kneedler, MD

142 The Pines

Davidson, NC 28036

Message:

Dec 3, 1993

Dear Khun Ratanaporn Sethakul:

Mr Gross of the CCT asked me to write an account of leaving Thailand in 1941. I have now done this and am sending a copy to you, too.

You have, I am sure, the 26 page booklet that Dr Ryburn published after his trip to Thailand in 1990-1. This describes our trip together, but is quite inaccurate. For instance he says I was not with the group for some time. He forgot that I was with him continuously from Chiangmai to the USA.

Cordially yours,

Harding Kneedler

For six months before World War II extended to the Far East, it seemed inevitable that it would do so. My wife’s parents, Dr and Mrs William Harris, retired heads of Prince Royal’s College, had retired in Chiangmai, planning to return to America with us. Because it was only a few months before we were due to return to the USA on furlough, I asked permission from the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions to send my wife Christina, our two small daughters, and the Harrises back to America in June, 1941, while I remained. This was granted.

On a visit to Bangkok in September, a German friend there told me that the people had no idea what was in store for them, that Bangkok would be destroyed. Early in December, I was in Bangkok again. A Chinese friend, “I hope you get back to Chiangmai safely.” The next evening when I boarded the night express to Chiangmai, everything was as usual. When the train reached Denchai (Phrae), we learned that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor and had come into Bangkok. The Thai put up a token resistance for eight hours, then wisely gave in and joined the war on the Japanese side, but did not do so actively. This saved a great deal of destruction, for otherwise Bangkok would have been damaged very badly, as my German friend predicted.

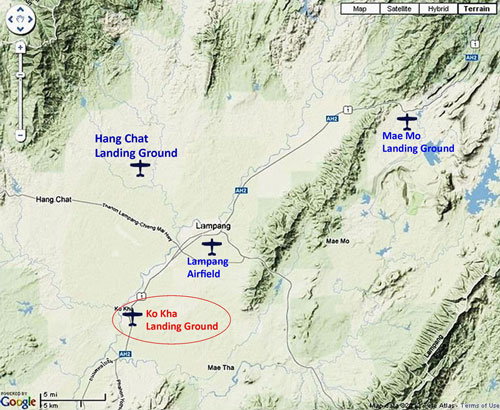

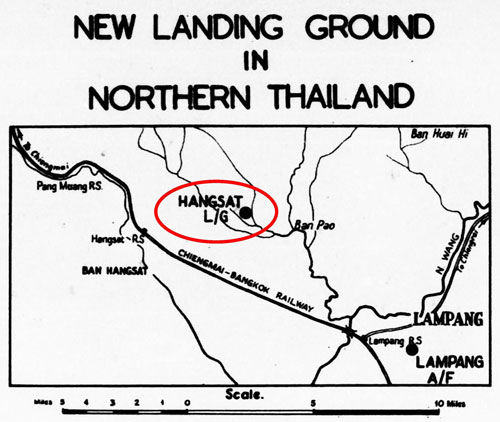

After a few days those of us in the north of the country received word from our consul in Bangkok that we should go to Burma. The only way possible was by a road from Lampang, through Chiangrai and on through the Burma border. Missionaries in Chiangmai, Phrae, and Nan had to go to Lampang by train because there were no roads to take them there. It became my task to arrange this, and it took me half a day. Long distance telephoning had to be done between the post offices. Some of the missionaries wanted to stay where they were and had to be persuaded. The Rev and Mrs Kenneth Wells, their two children, and the Rev and Mrs John Holladay and their two children went three days ahead of the rest and had no difficulties. The main group, after spending a night with the Hannas in Lampang, boarded buses which the Hannas had chartered for them and arrived in Chiangrai at 3 pm. An exit permit to leave the country could not be obtained that day because the government offices closed at three.

We spent the night in the home of Dr and Mrs Beach, who now joined our group. The main missionary group at this point consisted of 14 adults and 2 children: Dr and Mrs EC Cort, Hugh McKean, his wife and two children, Helene Newman, the Rev Horace Ryburn and myself (all from Chiangmai), Dr and Mrs Beach (Chiengrai), the Rev and Mrs Loren Hanna (Lampang), the Rev Gaylord Knox (Phrae), and the Rev and Mrs Bert Steward (Nan). In addition to our group of 14 missionaries, the Wells and Holladays had now reached Kengtung, 18 missionaries in all.

The next morning we could not get exit permits because the Governor was “in conference”. At noon an order came from Bangkok that no more aliens could leave the country. While we were trying to adjust to this news, an old American friend, MM Pittard appeared and asked me why I was sitting there. Mr Pittard, a tobacco expert from North Carolina, was a Thai government employee. I explained the situation to him and he said that he would see the Governor himself. When he came back, he told us, “It’s all OK.” The Governor had told him that he could go, since he was a government servant, but that the rest of us could not. Pittard said that we were there to help the country and suggested that the Governor could act as if he had not yet received the government telegram, and let us go. Moreover Pittard said that he would not go without us. The Governor acknowledged that we had indeed helped his country and gave Pittard the exit permits, which had already been prepared. Pittard now joined our group of refugees. (The Japanese were already in Lampang, and Pittard had gotten through them in the railroad station by pretending to be a German physician. He was carrying a medical bag and his servant did all the talking.)

We quickly rounded up the bus drivers and reached the border after dark. We carried our own limited baggage over the bridge into Burma and spent the night in a brand new bamboo rest house. Next morning we hired men to carry our baggage and had a litter made to carry Hugh McKean, who was crippled by a spinal cord tumor, and another litter for his two very small children.

After we had walked for a while, Dr Buker of the American Baptist Mission in Kengtung appeared. Those who had gone ahead had told him that we were coming. He had come to meet us with carts and drivers from his leprosarium. He told us that the bridge ahead of us was mined and we had better ford the river. If he had not come, we could all have been blown up. They took our luggage.

We spend that night in a schoolhouse sleeping on the floor. One of the party had a cold and sneezed a good deal. Half the party caught his cold. Next morning we started walking again, but a British truck which had brought supplies for the “free Chinese” (anti-Communist), picked us up and transferred us to another army vehicle which took us to Kengtung. Most of the party stayed there, later going on to India where Hugh McKean was operated on and his tumor found to be incurable. He died there. The others were brought later to America on a US naval vessel.

Horace Ryburn, Gaylord Knox and I spent only two nights in Kengtung, then headed for the US, first going by bus to Taungyi where there was a railroad. The bus trip took a day and a half on a narrow mountain road, with passengers sleeping in an open rest house during the night. The road was one way between Kengtung and the rest house, reversing its direction at noon, so that traffic could pass and continue on. The next morning we crossed the Salween River on a ferry large enough only for one bus. On the way up from the river, a back wheel came off because of a broken axle. If this had happened the day before, we could all have been killed, because there would have been a steep drop from the edge of the road and the bus would have gone down it. As it was, no one was hurt and soon an empty truck came along and picked us up. We reached Taungyi that day and Rangoon by train the next day.

We had a delay of a few days, trying to get permission to enter India. The three of us were in a government building making arrangements for leaving the country when we heard the sound of many people hurrying down the steps. We soon learned that Rangoon was experiencing its first bombing by the Japanese. We had seen some bomb trenches outside the building and hurried out to get in them. On the way, we could see American “Flying Tigers” fighting Japanese planes. We huddled down in the trenches, but most of the city had no protection. After the bombing, the people were in panic. First aid stations were set up in the city and the wounded treated. After the bombing there was a great exodus from the city. We were booked on a ship for Calcutta that was to leave early the next morning. Our consul sent a jeep to take us to it, but most passengers did not get there because no transportation was available.

The ship did not allow us on deck while it was in port. A defective electric fan mimicked the sound of an airplane and I thought we were going to be bombed again. But there was no more bombing. The next day was Christmas. The captain, an Englishman, was the only Caucasian on the boat besides us. He invited the three of us to Christmas dinner on the bridge with him. This was a very pleasant occasion for us.

In Calcutta, Ryburn and I caught a train for Allahabad, where a college friend of my father, a missionary, had been murdered long before. From there Ryburn and I crossed India by train to Bombay and then went by ship to Cape Town. Knox had stayed behind in India.

We tried to get train tickets to Johannesburg but were told that all seats were booked for some time ahead. I then answered an ad in the paper saying that someone wanted passengers to share expenses in driving there. This man was good company, but he wrecked his car on the way. I had only minor injuries; the driver and Ryburn were unhurt. It was dusk. We decided to “bum a ride” if possible. I held up my hand and a car stopped. It was our friend’s brother-in-law on his way to Cape Town. He took us to the nearest town ten miles away and we spent the night in a hotel. In the morning the train that we had wanted to take came through. Our friend said we would have no trouble getting seats on it and that if we had known the customs of the country, we could have gotten seats in the first place. A bribe had been expected. When the train came, he got us a compartment without any trouble simply by asking for it and saying he would pay what was suitable.

From Johannesburg we flew to Stanleyville in the Belgian Congo (Zaire) and after a week got passage on a plane to Leopoldville, the capital. We had to stay there in a mission guest house for ten days before we could get a plane to Lagos in Nigeria. The mosquitoes were bad there, and our missionary hosts said they considered that they were infected with malaria every night.

The next leg of our trip was by Pan-Am flying boat across the South Atlantic to Brazil, and from there we flew to Trinidad. After a week we got a plane on to Miami. On the way, this plane got caught in a downdraft and dropped so fast that things fell up out of our pockets. This gave everyone a good scare.

The rest was easy, a train direct to Philadelphia and home. The trip had taken almost three months.

| ID RTA units going thru Lampang on way to Kengtung | |

| ID IJA units going thru Lampang on way to Imphal | |

| Provide timeline for RTAF, IJAAF units assigned to Lampang | |

- Conventional Signs, Military Symbols, and Abbreviations (Washington: War Department, October 1943), p 23[↩]

- Map and Aerial Photograph Reading Complete (Harrisburg: Military Service Publishing, 1943) [Internet Archive] (offsite link), p 14[↩]

- ibid, p 13.[↩]

- ibid, p 24.[↩]

- ibid.[↩]

- ibid, p 34.[↩][↩]

- ibid, p 53.[↩]

- ibid, p 76.[↩]

- unpublished manuscript in Prince Royal’s College Archives, 1991[↩]