1930-1942: During this period, Tanaka became more and more involved with the IJA as preparations were made in the eventuality of a Japanese presence in Thailand and an invasion of British Burma.

1930: In Bangkok, Shu Hatano had worked for 16 years in the photo shop of his brother, Shozo Hatano. In 1930, Shu was approached by an IJA Colonel Kanji Tsuneoka who pressed Shu to accompany him to Chiang Mai where the colonel was to meet Tanaka; the colonel identified himself as a military attache at the embassy in Bangkok. Shu was acquainted with Tanaka from his trips to Bangkok to purchase photographic supplies. Obviously there would have been some discussion between the colonel and Shu’s brother, and possibly Tanaka, regarding the use of Shu. 1 There is some evidence that the colonel looked upon Shu Hatano as a potential assistant.2

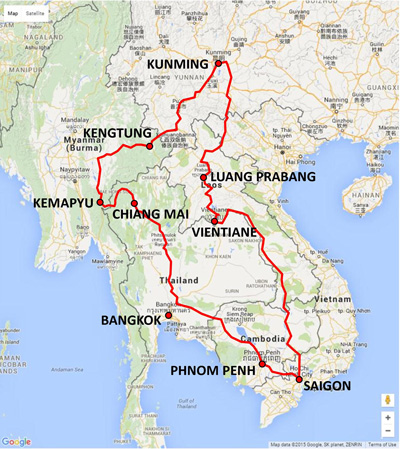

In August, the colonel and Shu journeyed to Chiang Mai. Tanaka left his shop in the hands of the just arrived Shu and disappeared with the colonel for “many days”. In the late 1980s, Shu recalled that Tanaka told of having traveled around Burma, Laos, China, Vietnam, and Cambodia with the colonel, collecting information.2 If one journey had covered all objectives, a very broad brush itinerary for a hypothetical journey might have been:3

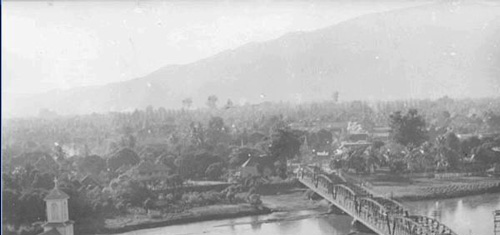

Moving clockwise from Chiang Mai to Kemapyu-Kengtung-Kunming-Luang Prabang-Vientiane-Saigon-Phnom Penh, 6,000 km on foot / horse / motor vehicle to Aranya Prathet, plus 1,000 km more by rail from Aranya Prathet back to Chiang Mai; for a total of 7,000 km. At that time, land travel was often over trails such as this:4

The distance over roads of this type could represent about 200 days, which would certainly constitute Hatano’s “many days”.5

The motivation for this effort was probably uncertainty about a growing conflict in China between the forces of Mao Tse Tung and Chiang Kai-shek, and about the intentions of Britain and France whose possessions bordered Siam. An additional motivation was evaluating a potential road route from Chiang Mai through Mae Hong Son and connecting to, probably, an existing road at Kemapyu in Burma. With the return of the pair, Shu got the impression that thereafter Tanaka always had a reliable supply of photographic materials and equipment6 (however, Hatano made this observation with no idea of what might have transpired between Tanaka and the IJA, prior to his (Shu’s) arrival in Chiang Mai in 1930).

1931: In April, Colonel Tsuneoka was promoted to the army general staff and left Siam.7

1933: In accord with an agreement with either the colonel or a successor,8 Tanaka began a “terrain survey” along the Burmese border. The assignment apparently included setting out a route where none had existed between Chiang Mai and Mae Hong Son through Mae Malai and Pai — after the war, Tanaka’s effort would evolve into Thai Route 1095.9

If he traveled west at that time into Burma seeking a connection with Burma’s existing road system is not clear. However, IJA planning in 1943 for access from Chiang Mai to Burma mentions only Toungoo as a western terminus. Mae Hong Son is never mentioned in describing the road. Hence, it seems reasonable to assume that Tanaka did in actual fact venture into Burma, to connect with an existing Burma road (current Burma Rte 5) near Kemapyu:10

The distance between Chiang Mai and Kemapyu is about 385 km. At a walking speed of 3 km per hour,11 10 hours per day, Tanaka would have taken 13 days just to get to the far end of his project, plus an equal interval to get back, plus time expended in survey work. It seems to have been a one-man assignment, and, as such, it was necessarily long term.

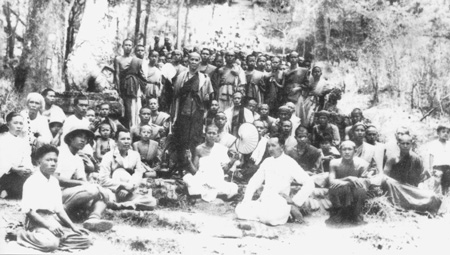

1935: Tanaka was in Chiang Mai to record the dedication of the road to Wat Doi Suthep, built by the monk, Kruba Sriwichai:12

1939: Shu Hatano married Tanaka’s daughter, Kumpoon.13

Between 1930 and 1939, Tanaka performed “many surveys” in Laos.14 Matsumoto recalled a photo that Hatano had shown him, and which the author duplicated in his book, of Tanaka dressed in Laotian clothing with a Japanese medal on his chest. The photo was dated “immediately following WWII”, in Chiang Mai.15

1940-1941: From October 1940 to May 1941, Siam fought French forces in French Indochina in an attempt to regain control of territory lost during King Chulalongkorn’s reign. The war was characterized as a defeat for Siam on the sea, but a victory in the air. Japan chaired peace negotiations, and ensured that France returned all the disputed territory to Siam.16

For an indeterminate number of years prior to the Franco-Thai War (1940-1941), Tanaka had traveled at least once a year to Saigon at the request of an embassy military attache. Hatano recalled that Tanaka’s photo subjects had seemed to center on French warships.17

1941: “In mid-March, Tokyo ordered the opening of another [consulate] in . . . Chiang Mai . . . . the new offices were designed primarily as intelligence-gathering posts.”18

In February, representatives of the Minami Kikan [Minami Organ (organ as in organization)], an independent arm of the IJA, had been charged with supporting and liaising with the Burma Independent Army (BIA). Among their objectives was setting up liaison points on the Thai-Burma border.19 Four liaison points were subsequently set up, with the most northerly of them being Chiang Mai.20 There it functioned as a commercial, mining, forestry, and / or development organization which allowed it the freedom to investigate remote areas.21 Tanaka would not have been designated the Minami Kikan representative in Chiang Mai for its members had been carefully selected and specially trained in working with the BIA in Burma in combat conditions. However, tasks set out for the Minami Kikan effort included “reconnaissance . . . to be made of the topography and roads from the Thai border into Burma, and a military geography compiled.”22 For this last, it would appear that Tanaka must have been a major resource for the Minami Kikan: thus he would have been quite busy during most of 1941.

July 1941:

In various despatches to FO [Foreign Office], Crosby [der britische Gesandte Josiah Crosby, 1880 – 1958] reported Japanese infiltration. An obvious one was in July when a Japanese Camera Department came and sent out teams of photographers to record the “cultural entente” between Thailand and Japan. A secret source imparted that a complete list of films already produced included highways, anti-aircraft facilities in Thailand, aeroplanes, the salt industry, British firms in Thailand and various government workshops. Crosby commented that Thai Government probably knew but dared not oppose it. Then came the Increase in Japanese tourists to Thailand, especially in the south, in October 1941.23

On 01 December (?), a Mitsui employee in Bangkok recalled that Japanese residents were called together “several days” before the “invasion” to be told that the IJA would invade on 08 Dec 1941. Whether this information found its way to Chiang Mai is unknown.24

08 December: IJA troops entered Thailand.

15 December: IJA personnel first appeared in Chiang Mai.25 Boonserm recalls that Tanaka was at the railway station to greet the first IJA troops to arrive. It is apocryphal that Tanaka was wearing a uniform when he met the first troops. However, Boonserm smiled at the story and said such was not the case. Boonserm, 13 at the time, did not claim to have been present at the rail station when the IJA troops arrived. His cousin, Wichit Jayavann, 17, claims to have been present and strongly asserted that Tanaka did welcome the incoming IJA troops in his own uniform, with rank of major.26 While Tanaka was obviously serving his country and his country’s army, he was not doing so in a military capacity. Had Tanaka been authorized to wear a military uniform at his age of 66, he would likely have been the most senior member of the IJA.27

- Matsumoto, p 195.[↩]

- Matsumoto, pp 74, 197.[↩][↩]

- Map image: Nations Online: Thailand. Distances from: Google Earth Ruler utility Whyte, BR, The Railway Atlas of Thailand, Laos and Cambodia (Bangkok: White Lotus Press, 2010), pp 29, 39.[↩]

- Payap Collection: extract from Image no. 23, undated, by unknown. Photo also appears in Sarassawadee Ongsakul, History of Lanna (transl by C Tanratanakul) (Bangkok: Silkworm Books, 2001), p 233 as No. 104 with caption “The road used by caravans in transporting goods”, dated 1942, and attributed to the National Archives of Thailand.[↩]

- That assumes a walking speed of 3 kph and a ten hours of walking per day. The duration would have been reduced if motor vehicles (bus service) were available on any stretch. (TrailTrove: Hiking Speed).[↩]

- Matsumoto pp 196, 197. [↩]

- Matsumoto p 198.[↩]

- Matsumoto, p 198.[↩]

- Matsumoto pp 75, 197, 198. The route chosen seems odd at first glance: there were existing routes, The Old Elephant Trail and the Hot-Mae Sariang-Khun Yuam, plus variations,[บุญเสิม สาตราภัย, ลัานนา . . . เมี่อตะวา (เชียงใหม่: ผลิตและจัดจำหน่ายโดย, 2007) [Boonserm Satrabhaya,The Yesteryear of Lanna (Chiang Mai: Bookworm Publishing, 2007)], p 175]. What was chosen had cobbled together various trails and footpaths which had never been a continuous route to Mae Hong Son. It is assumed to have been chosen because it offered better access to Siam’s northern border with Burma. In this effort, Tanaka established the routing of what is today labeled Thai Rte 1095.[↩]

- Map image: Nations Online:Thailand. Annotated by author using Microsoft Publisher.[↩]

- Or perhaps slower: this is the low end of an average range, to allow for steep slopes, poor trail conditions, porters, the occasional photo, etc. (TrailTrove: Hiking Speed).[↩]

- Payap University Collection, no. 107. Dated as 30 April 1935 per Wat Doi Suthep Official Website (accessed 2013, but no longer exists in Nov 2015).[↩]

- Matsumoto, p 229.[↩]

- Matsumoto, p 85. Note that Matsumoto (and / or Hatano) is ambiguous in describing the nationality of the costume as Vietnamese or Laotian (pp 30, 33, 85, 197).[↩]

- Matsumoto, p 30.[↩]

- Wikipedia: Franco-Thai War (link confirmed 12 Aug 2015).[↩]

- Matsumoto, p 83.[↩]

- Reynolds, EB, Thailand and Japan’s Southern Advance (New York: St Martin’s Press, 1994), p 66.[↩]

- Tatsuro, Izumiya, The Minami Organ (Tokyo: Tokyo Shoten, 1967), translated by U Tun Aung Chain, 1981, pp 25-27.[↩]

- Ibid, p 37. The other three were Rahaeng (Tak) leading to Mae Sot, Kanchanaburi which eventually led to the Death Railway, and Ranong which became the endpoint for the Kra Railway.[↩]

- Lebra, JC, Japanese-Trained Armies in Southeast Asia (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2010), p 59.[↩]

- Ibid, p 27.[↩]

- Charivat Santaputra [จริย์วัฒน์ สันตะบุตร]: Thai foreign policy 1932-1946 (Bangkok: Thai Khadi Research Institute, Thammasat University, 1985), p 262; per Chroniks Thailand (link confirmed 12 Aug 2015).[↩]

- Roberts, JG, Mitsui: Three Centuries of Japanese Business (Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1973), Ch 24 (no longer available on-line).[↩]

- Chainilphan, MR, “Chiang Mai Skies during WWII”, Thai News (Thai language newspaper), 18 Dec 2009.[↩]

- Discussion with Wichit Jaravann 18 Aug 2017.[↩]

- For example, the senior IJN admiral, Isoroku Yamamoto, was one of oldest who was still active and he was aged 57. IJA uniforms had been handed out to many Japanese civilians in the months prior to the war, per David Boggett (discussion[↩]