1875-1896: Morinosuke Tanaka was born on 23 August 1875 in Kagoshima,1 on the most southerly of Japan’s four main islands, Kyushu. His birth came only 21 years after US Admiral Matthew Perry, with his ominous “Black Ships”, forced Japan to sign the Convention of Kanagawa. That agreement eventually led in 1868 to the beginning of the Meiji Era which was characterized by a huge national effort to modernize Japan.

But the era did not start smoothly: Kagoshima, then known as Satsuma, was an independent minded province, and did not willingly accede to the new Meiji government. In 1877, in the Satsuma Rebellion, the province unsuccessfully revolted against Tokyo. Tanaka’s father, as a minor samurai in the Satsuma Clan, participated in that revolt.2 For his actions, the father was imprisoned for three years in Tokyo. He was then released with seemingly no prejudice, possibly because he was a lower level samurai.3 Morinosuke was heir to this tradition of independent thinking.4, and male chauvinism (p 87 (typical)).))

His father established a photo shop in Tenmonkan City5 in Kagoshima Prefecture and by 1893, if not before, Tanaka (aged 18) was working there.6 Thus he early developed a familiarity with many aspects of photography.7

Early in 1896: Tanaka at this time was portrayed as “young and eager for adventure”: he had probably been swept up by the momentum of new ideas accompanying the Meiji Era. He announced to his family that he wanted to go to Formosa (Taiwan) to study photography.8 What Formosa offered that his work in Kagoshima had not already provided was not explained. Formosa had only recently been occupied by Japan per the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki which settled the First Sino-Japanese War. Formosa was viewed as largely rural, with an agrarian economy focused on growing sugar and tea.9 It did not appear to his family to be an ideal place to study photography, with Shanghai10 being generally favored for gaining experience in that field.11 Despite entreaties from his family, he persisted, and with the support, both in spirit and financially, of a well placed “friend”, Kyukai Arikawa (有川九介),8 Tanaka departed, ostensibly for Formosa.

1896-1902:12

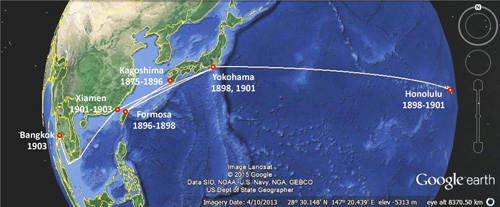

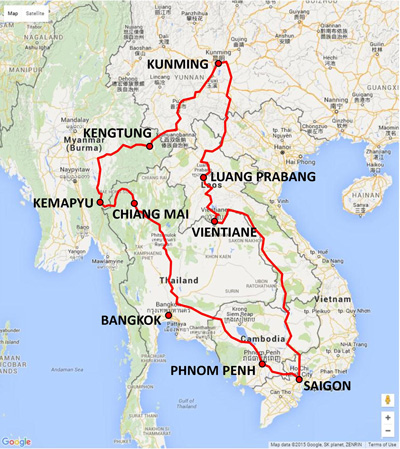

A possible reconstruction of Tanaka’s extended journey to Siam 13

Tanaka’s life, up to his departure for Formosa, is reasonably well documented by Matsumoto, based on family interviews. In contrast, for the period after Tanaka’s departure until he arrived in Bangkok, there was only Tanaka himself for a source. As implied above, family members interviewed by Matsumoto had been skeptical about his claimed interest in studying photography in Formosa,14 and a letter from him during his time in Formosa indicated that he had become involved in something else.15 Matsumoto concurred in the family’s skepticism, and pointed out that Tanaka had never offered any but the sketchiest of detail about his time in Formosa or in Xiamen.15 Boonserm Satrabhaya, another source, was also extremely vague about that period.16 There is a possibility that Tanaka never went to Formosa (see below).

Tanaka’s comments about this period seem to have disclosed only:17

1896: He departed for Formosa to study photography.

1901: Unhappy with Formosa, he moved to Xiamen.

1902: He moved to Bangkok.

These facts were recorded in a newspaper interview in 1907.18 Subsequently, two events from that period, which Tanaka apparently never intended for public disclosure, surfaced:

Before he arrived in Siam, he had worked in the (Japanese) Army Chiefs of Staff map department (more properly the Land Survey Department of the General Staff Headquarters).19 He divulged this to his (future) son-in-law, Shu Hatano, sometime after Shu started working with him in 1930 in Tanaka’s Chiang Mai photo shop.

A US Immigration document records that a Morinosuke Tanaka disembarked in Honolulu in 1898.20 While the surname, Tanaka, is very common in Japan,21 the given name, Morinosuke, is definitely not. Hence it is plausible that this was the same individual that is the subject here. In addition, the date of arrival fits nicely into a period otherwise vaguely defined for Tanaka.

The conclusion to draw here is that Tanaka’s failure to provide details about this period was intentional. And that intentionality, coupled with the two rich insights above about his activities during that period, begs for speculation. Note that without this information, Tanaka might today carry only the reputation he apparently intended.

Later in 1896: So, Tanaka perhaps went first to Formosa.

While Formosa was judged perhaps primitive because of its economy based on sugar and tea, China had seen it as an important link in its defense network and had invested heavily in its infrastructure development as well as its defense facilities. 22 Most notable was the installation of modern Armstrong breechloader guns at various coastal defense facilities on the island, but at no other location in China at that time.23 That buildup had been prompted in part by Japan’s many efforts to take over the island starting in 1592, as a part of a policy which, in Tanaka’s early life, had matured into its Southern Expansion Doctrine: 24 Formosa was seen as a stepping stone to Southeast Asia.25

The strengthening of Formosa’s defenses was also partly the result of the Sino-French War in 1884-1885; China had won that war, but the conflict had emphasized to China the importance of the island in its coastline defense system.26

In this later conflict in 1895, the First Sino-Japanese War, which China lost, Japan had acquired Formosa as part of a settlement with China.27 The victory contributed to Japan’s military and citizenry regarding their nation as invincible.

If Tanaka did go to Formosa, he would have arrived in time to witness Japanese Army tactics in fighting a guerrilla resistance, tactics which were characterized as having “perpetrated all the worst excesses of war”. 28 Whether working in a land survey function or as a photographer, he would likely have been too late to have contributed to a series of 1:200,000 scale topographic maps of Formosa which were published in 1897 under the direction of the Japanese General Staff Headquarters.29 More likely, he would have been part of an early effort collecting data for a new series of larger scale topos of Formosa, whose publication started in 1913.

1898: Tanaka then went to Hawaii where Japan had special concerns:

Contract labor: After the early failure of an 1868 effort to import Japanese labor to work its sugar cane fields, the Kingdom of Hawaii had restarted importing Japanese labor based on an understanding which was formalized in 1886.30 By 1894, 29,000 Japanese Nationals were present in Hawaii (growing to 61,000 by 1900).31 Their mistreatment by US commercial sugar companies was appalling, judged by even the standards of the period,32 and this became known to the Japanese government. With the overthrow of the Kingdom in 1893 by a cabal of US sugar interests, the position of those workers became more uncertain and raised deep concern in Japan. 33 That concern could have resulted in Tanaka being assigned to provide an on-the-ground assessment of the situation.

Strategic interests: The US Navy’s evolving theory of sea power had alerted Japan to the strategic significance of Hawaii in the Pacific in 1890.34 The overthrow of the Kingdom government in 1893, followed by commercial interests lobbying the US Congress to annex the islands35 roused Japanese concern, and Hawaii became a major focus of the Japanese government.36 Tanaka’s arrival in Honolulu in 1898 could be interpreted as having been some part of that focus. Curiously, two days before Tanaka landed in Honolulu, the US formally annexed Hawaii.37

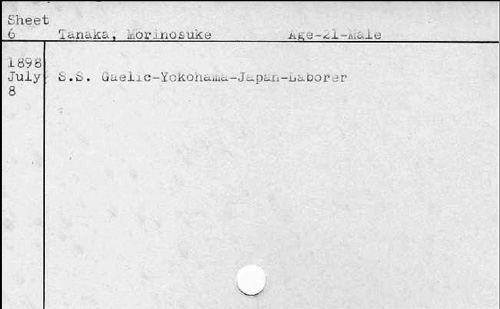

So, in 1898, a secretive Tanaka boarded the SS Gaelic 38) bound for Honolulu, to all appearances a Dekasegi” (出稼ぎ), a common laborer:

So, in 1898, a secretive Tanaka boarded the SS Gaelic 38) bound for Honolulu, to all appearances a Dekasegi” (出稼ぎ), a common laborer:

“. . . a Japanese worker who plans to return to [his] homeland after making money in a foreign land . . .”. An example of agricultural work: “Sugar plantations in Hawaii (3 year contract)”.39

He arrived in Honolulu to be recorded as passing through US Immigration on 08 July 1898 as a laborer per this file card:40

Tanaka’s Immigration Card for Honolulu

While Tanaka was actually age 22 on this date, the 21 on the file card might reflect a confusion about East Asian age reckoning where a person’s age at birth was assumed to be one; in contrast, the Western system assigns an age of zero at birth. Possibly an immigration officer mistakenly tried to correct Tanaka’s stated age — which Tanaka had already corrected to the Western standard. Another possible source of confusion might have been trying to convert Tanaka’s birth date from the Meiji calendar to the Gregorian calendar, that transition having occurred in 1873, two years before Tanaka’s birth.41

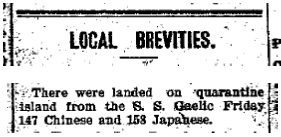

“Yokohama” appears on the card because it was the port-of-call previous to Honolulu. What the itinerary of the SS Gaelic was has not been found; but the ship is recorded as having been in Nagasaki in 1898,42 so where Tanaka had actually boarded the ship is uncertain. On 12 July 1898, the Hawaiian Gazette recorded that 158 Japanese from the SS Gaelic were on Quarantine Island:43

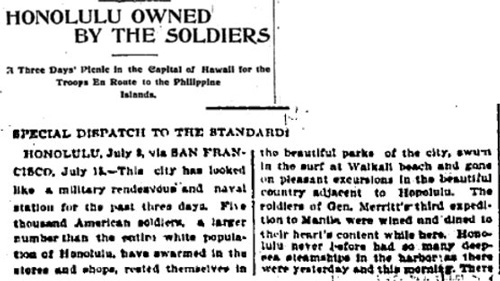

From Quarantine Island, they could view the town of Honolulu, across a kilometer-wide dredged ship channel.

From Quarantine Island, they could view the town of Honolulu, across a kilometer-wide dredged ship channel.

Concurrently, Honolulu was being inundated by US Navy personnel on their way to secure the Philippines after Dewey’s lopsided victory in the Battle of Manila Bay, a part of the Spanish-American War. This new American foothold in Southeast Asia could only have bonded Japan more firmly to its Southern Expansion Doctrine44

There is no information regarding Tanaka’s activities in Hawaii. Japanese army maps of Hawaii offer no clue: those available in Japanese archives were published by the Ordnance Survey Department of the Japanese Chiefs of Staff in 1942 (after the attack on Pearl Harbor). They were based on US State Department topographic maps issued between 1911 and 1930,45 which were, “as is”, quite adequate in detail. Japanese map makers’ primarily contribution appears to have been providing map legends in Japanese.46

Tanaka’s objective was probably unrelated to mapmaking, but rather, as suggested above, to observation and reporting on working and living conditions of Japanese laborers employed on the Islands after the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii in 1893, or something to do with an assessment of US military preparedness. It is even possible that he “escaped” from the island and traveled to the US Mainland to evaluate how that connection functioned.47

Last Updated on 29 February 2024

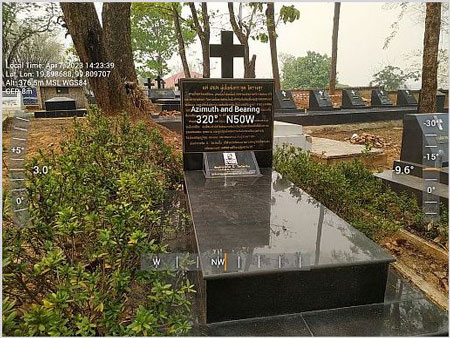

- His cemetery marker at Wat Tha Satoi in Chiang Mai reads 1873, which is in error. (Matsumoto, pp 89, 118, 229).[↩]

- Matsumoto, p 100. In the Satsuma Clan, the tradition of independence was very strong: in 1865, defying a Tokyo edict to maintain the nation’s isolation, the Satsuma clan smuggled 15 sons to the UK to learn Western ways (Wikipedia: Nagasawa Kanaye) (this might have been a model for sending five girls to the UK in 1871, as described in Barbara Chai’s Daughters of the Samurai). In 1877, Saigo Takamori, the leader of the clan and, as “the last true samurai”, faithful to the code of the samurai, died in the same rebellion that put Morinosuke’s father in prison.[↩]

- Matsumoto, pp 119, 120.[↩]

- Matsumoto, however, repeatedly suggests a Tanaka hardened by Japan’s sense of imperialism (p 85 (typical[↩]

- Matsumoto, p 78. Boonserm, pp 50-52.[↩]

- Boonserm, p 53.[↩]

- Boonserm, pp 50-52.[↩]

- Matsumoto, p 120.[↩][↩]

- Matsumoto, p 191.[↩]

- However, the Sino-Japanese War had just ended; Chinese animosity directed towards Japanese was at a high and forced another Japanese photographer, Kaishu Isonaga, out of business in Shanghai and to relocate to Bangkok, where Tanaka met him in 1903 (Matsumoto, p 24).[↩]

- Matsumoto, pp 40ff, 121.[↩]

- This period in Tanaka’s life is covered here in greater detail because the detail was not known when Matsumoto and Boonserm published.[↩]

- Google Earth view centered on N28° E150° at eye alt 8370km. Image captured with Gadwin PrintScreen, enhanced with IrfanView and annotated with Microsoft Publisher by author. Date sources: 1875, 1896 Kagoshima:Matsumoto, p 229. 1896 Formosa: ibid. 1898 Formosa, Yokosuka, & Honolulu:Hawaii Gov’t Archives, accessed 15 Jul 2011. 1901 to Xiamen: Matsumoto, p 229. 1902 Xiamen, Bangkok Matsumoto, p 229.[↩]

- Matsumoto, p 121.[↩]

- Matsumoto, pp 122, 190.[↩][↩]

- To be fair, it must be noted that Boonserm’s position was that of an apprentice learning the skills of photography from a master, in this case, Hatano. Hence Boonserm would not have been motivated to critically evaluate any comments by Hatano.[↩]

- Matsumoto, pp 122, 229.[↩]

- Matsumoto, pp 190, 191.[↩]

- Matsumoto, p 25.[↩]

- See file card illustration below[↩]

- Tanaka is the fourth most common surname in Japan (Wikipedia: List of most common surnames in Asia: Japan, accessed 12 Aug 2015). No list of given Japanese names was found on the Internet — in English anyway.[↩]

- Wikipedia: Taiwan under Qing rule, accessed 12 Aug 2015.[↩]

- YC Chen msg of 1737 hrs 13 Oct 2015, in Axis History: Chinese military installations in Taiwan in 1895[↩]

- Wikipedia: Nanshin-ron, accessed 12 Aug 2015.[↩]

- Wikipedia: The Treaty of Shimonoseki: Taiwan, accessed 12 Aug 2015.[↩]

- Wikipedia: Hobe Fort, accessed 12 Aug 2015.[↩]

- Wikipedia: The Treaty of Shimonoseki: Treaty terms, accessed 12 Aug 2015.[↩]

- Wikipedia: Taiwan under Japanese rule (accessed 01 Oct 2015), quoting The Cambridge Modern History of 1910.[↩]

- Gaihozu Map Digital Archive, (search on “Taiwan”), items 36-49. It is not clear if the IJA actually performed a land survey for that map series, or merely updated existing Chinese maps of the area.(query to Axis History Forum, Early topo mapwork for Taiwan, produced no response). China’s accelerated development of infrastructure on the island in the 1870s-1880s (see notes 12a and 12b above) would likely have been accompanied by a substantial mapping effort.[↩]

- Hawaiian-Japanese Labor Convention of 1886″ (Ogawa, Dennis M, and Glen Grant, Kodomo No Tame Ni-For the Sake of the Children: The Japanese-American Experience in Hawaii (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1980), p 6ff).[↩]

- Wikipedia: Robert Walker Irwin: Kanyaku Imin, accessed 12 Aug 2015.[↩]

- Hawaii: Life in a Plantation, Library of Congress website: Japanese Immigration.[↩]

- Ogawa, ibid.[↩]

- Wikipedia: Alfred Thayer Mahan: Japan, Wikipedia, accessed 12 Aug 2015.[↩]

- Wikipedia: Overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, accessed 12 Aug 2015.[↩]

- Wikipedia, ibid, accessed 29 Aug 2011.[↩]

- Wikipedia: Hawaii, Annexation, accessed 12 Aug 2015.[↩]

- Apparently this was the RMS Gaelic, of 4200 tons, chartered to the Occidental & Oriental Steamship Company:Tanaka was lucky: a month and a half later, the ship ran aground (14 Aug 1896) at Shimonoseki and had to be towed to Nagasaki for repairs. (Wikipedia: RMS Gaelic, accessed 16 Oct 2015[↩]

- (Sanders, Maia, Temporary and Seasonal Migrants (Japanese in Pacific, accessed 12 Aug 2015). But the term also applies to Brazilians migrating to Japan for work; see Wikipedia Dekasegi, accessed 12 Aug 2015.[↩]

- US Immigration Card for Honolulu, accessed 15 Jul 2011.[↩]

- Japanese calendar (link confirmed 12 Aug 2015): Meiji era changes. As a part of its modernization effort, Japan moved from a lunar calendar to a Gregorian calendar amid much confusion. Tanaka’s birth date as recorded at his memorial in Wat Tha Satoi in Chiang Mai errs the other direction recording 1873, two years before the date in the Tanaka family register (Matsumoto, pp 25, 229).).[↩]

- SS ‘Gaelic’ at Nagasaki (link confirmed 12 Aug 2015).[↩]

- With some irony, Quarantine Island, renamed Sand Island, served as an internment camp to temporarily house Japanese-Americans in the early part of World War II (Wikipedia: Sand Island link confirmed 12 Aug 2015.) Quarantine Island no longer exists: it was “swallowed up” with the dredging that created Sand Island.[↩]

- Syracuse Semi-Weekly Standard, 19 Jul 1898, p 4, Newspaperarchive.com (by subscription).[↩]

- Gaihozu Map Digital Archive, (search on “Hawaii”), items 1-62.[↩]

- For example, see ホノルル (Honolulu).[↩]

- Immigration-Japanese, Hawaii “Life in a Plantation society” (link confirmed 12 Aug 2015): . . . thousands fled to the mainland before their contracts were up.[↩]