01-02 January or 03 – 05 February 1942 (?): The first impact of the war on Mae Hong Son was recalled as having occurred early in 1942. From 1998 interviews with Sgt Major 3rd Class (SM3, retired) Kawila Chanopas, and his wife, Jawla:

Around 1500 hours on 01 or 02 Jan 1942, Allied aircraft flew . . . past Doi Kong Mu [the mountain overlooking Mae Hong Son from the west] and dropped a bomb on Mae Hong Son Bridge. . . . One policeman was killed by the bomb at the bridge. 1

There is, however, no Allied Forces record indicating that its aircraft bombed Mae Hong Son on 01 or 02 Jan 1942. The first Allied record that the town had been attacked is dated 03 Feb 1942, a month later, by a single Indian Air Force (IAF) bomber with RAF fighter escorts. Bombing of a bridge is not included in the bomber pilot’s report for that attack (see report for 03 Feb 1942 below). Additional attacks with several IAF bombers occurred on the next two days (see reports for 04 Feb and 05 Feb 1942 below).

To add to the confusion, or possibly to demonstrate a problem with oral history, there are two reports of other bridges in the area being bombed, neither confirmed, nor even likely — it is assumed that the reports actually refer to the more probable 03 Feb 1942 event:

According to Mr Porm Sootsukon (a civil servant in Mae Hong Son) around 1235 hours on 05 Mar 1945, a single two-engined Allied Forces plane from the direction of Burma . . . went on to bomb a bridge over the Mae Hong Son River, two km from Mae Hong Son’s center. Two bombs landed 15 m from the bridge. The plane flew back and the pilot waved a handkerchief. After the plane left, inspection determined nothing had been damaged. It was assumed that the intent of the bombing was just psychological in support of the Free Thai movement. 2

If, in fact, the bridge had been targeted, perhaps a pilot was just unloading bombs on a “target of opportunity” because he could not attack his assigned target. However, the more obvious target of opportunity would have been the airstrip. But then, because of the lack of accuracy of bombing in that era, it is quite possible that the pilot might have been aiming at the airfield and instead hit the bridge, well to the right of the approach path.

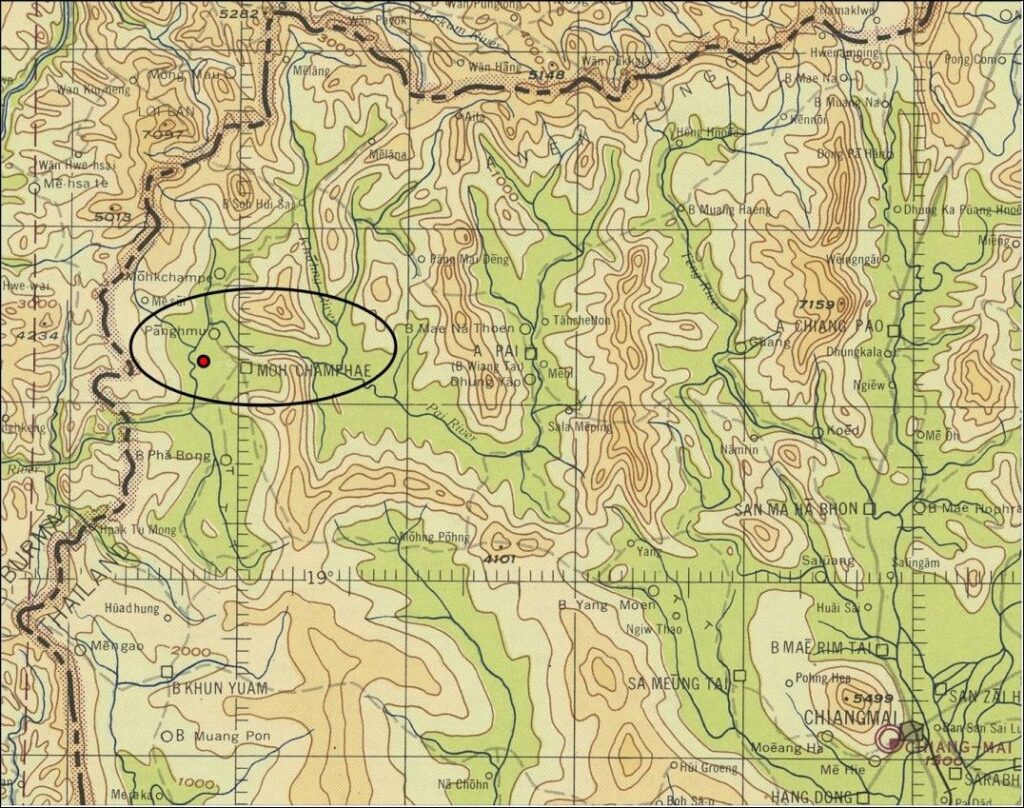

Mr Yen Waraporn, (65 years old [in a 1998 interview]) stated that the Japanese Road [future Thai Route 108, connecting Mae Hong Son to Mae Sariang] crossed Mae Samat Stream with a log bridge capable of supporting vehicles (current location: ~N19°11.33 E97°59.02). Later, this bridge was bombed and damaged. This bridge was about 13 km south of Mae Hong Son. 3 No date was specified, but work on the “Japanese Road” was only started in mid-1943 and completed in that area in early 1944. So, in this case, neither location nor time coincide.

It is assumed that the January dates from the first witnesses on the ground were in error and that the attack(s) they witnessed occurred during the period 03 – 05 Feb 1942. Two bridges are currently in the immediate area and bridges were probably at those same locations in 1942: 4

The bridge over Pu Stream (N19°18.47 E97°57.86) is just 300 m (950 feet) to the left of the approach path for the westerly end of the Mae Hong Son airstrip and is the more likely candidate for a stray bomb. Such a deviation would easily have been possible in 1942, given the limited bombing accuracy available at that time. 5 Bombing Accuracy in a Combat Environment puts it in perspective:

Those who have not delivered weapons from an airplane have little or no conception of the problems involved or the requisite skills. There are so many variables in the accuracy equation and the chance for error is so great as to make one wonder how fighter pilots do as well as they do.))

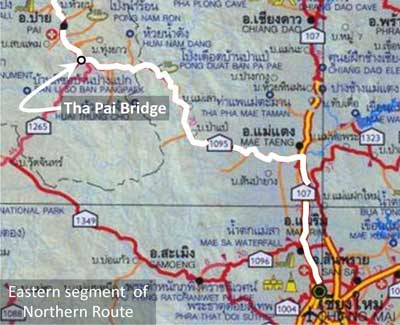

11-12 January 1942: Three Corsairs from [Royal Thai Air Force Squadron] 32 bombed a small Burmese village across the border from the Thai town of Mae Hong Son where enemy troops had been reported. 6 The Corsairs flew out of Chiang Rai, where they had been transferred only a few days before from first, Korat, and then Lampang. 7 Having flown from Chiang Rai, the squadron’s flight was probably visible from Mae Hong Son.

23 January 1942: RAF 67 Squadron Brewster Buffalo aircraft (quantity unspecified) “recced” [flew reconnaissance over] Mae Hong Son. 8

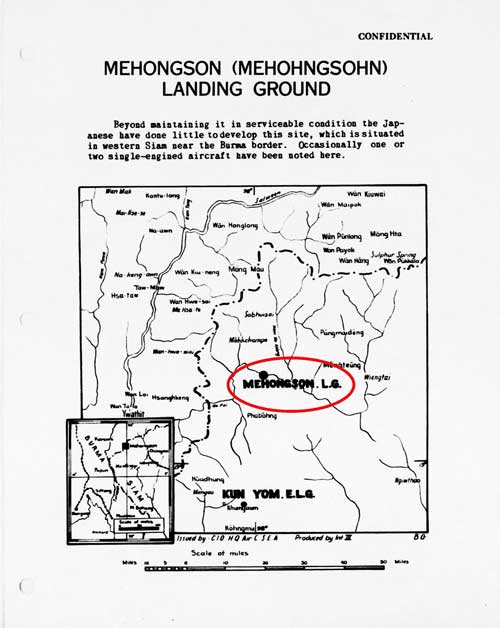

February 1942: A British General Staff map of Burma rather crudely locates the Thai border town of Mae Hong Son (Me-hohngsohn): 9

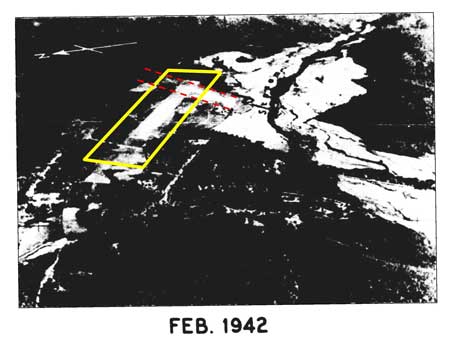

February 1942: An oblique aerial view, looking southeast at Mae Hong Son airstrip: 10

There is no comment in the airfield report about the photo; however, it is clear that a crosswinds runway was either under construction or perhaps completed, though the view of the far end in this case might have been obscured by the poor quality of the image. In either case, work on that crosswinds runway would almost certainly have been done by Thailand’s Aerial Transport Company, not the IJA. The quality of the photo is very poor because it is a microfilm copy of a printed publication, itself of unknown quality. 11.

01 February 1942: The Toungoo Airstrip in Burma was attacked by the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force (IJAAF):

In the early hours of the morning . . . the 5th Hikoshidan commenced a series of four raids using between six and fifteen bombers, inflicting considerable damage . . . . 12

The attack is relevant to the Mae Hong Son airstrip because the IJAAF aircraft in the attack were believed by some to have flown out of that location. 13 But that was improbable on the face of it, because the minimal facilities there would not have been adequate to support that number of aircraft simultaneously.

At this time, military intelligence appears not to have been well developed. In a few days, 10 February 1942, United Press would report:

Military sources . . . said . . . the Japanese were concentrating at Chiengmai, Thailand, for an offensive aimed at Toungoo, 175 miles due west. 14

And later, 18 February 1942, the Associated Press would report:

. . . the RAF carried out a mass attack on a Thailand rail terminus in the north which the enemy is believed using as a base for a parachute invasion of territory vital to the supplying of China. . . . The raided parachute invasion base was Chiengmai . . . The Japanese also are believed to have parachute troops and air-borne infantrymen at Mehongson . . . and at Mesarieng . . . [possibly] to break through to Toungoo . . . 15

Presumably this information was available earlier within the military system and would have been justification for suspecting Mae Hong Son. As it turned out, military sources were simply wrong regarding activities in both Chiang Mai and Mae Hong Son.

03 February 1942: Probably using the erroneous intelligence report as a guide, a Westland Lysander from Indian Air Force (IAF) 1 Squadron piloted by Sqn Ldr KK Majumdar and escorted by two RAF 67 Squadron Buffalos attacked the Mae Hong Son airfield. A hangar was reported destroyed. 16

. . . [IAF] Squadron Leader Majumdar [in a Lysander] . . . flying in low . . . attacked the airfield’s only hangar, which contained an aircraft, scored two direct hits, and returned to Toungoo. 17

[Victor Bargh in an RAF Buffalo] was . . . escort [to] a Lysander attacking . . . (Mae Hong Son) airfield . . . [His] logbook reported:

“Jumbo [the Lysander] dropped a couple of 250s [pound bombs] on hangar — busted it. I strafed surroundings”. 18

04 February 1942: The whole of the IAF 1 Squadron Lysanders without escort repeated the strike on Mae Hong Son: [relying on camouflage and their ability to fly at treetop height to avoid the attention of patrolling Japanese fighters] . . . 19 The patrolling aircraft would have been Royal Thai Air Force Squadron 22 with Vought Corsair biplanes, flying out of Chiang Rai, which had been assigned to surveille Burma’s Shan States 20

. . . They scored direct hits on airfield buildings and a wireless station, 21 besides some hits and near misses on aircraft dispersed round the landing ground. 22

Conversely, the Associated Press, monitoring radio broadcasts from Japan, quoted a Domei Japanese news report:

“. . . for the second consecutive day today” (04 Feb 1942), IJAAF bombers attacked Toungoo, damaging aircraft on the ground and hangars. 23

05 February 1942: IAF 1 Squadron without escort again attacked Mae Hong Son (this time with no damage report), and also Chiang Mai and Chiang Rai. 24

15 February 1942: IAF 1 Squadron, again flying from Toungoo, recced Mae Hong Son. 25

16 February 1942: IAF 1 Squadron, once again, flying from Toungoo, recced Mae Hong Son. 26

22 February 1942: IAF 1 Squadron flying out of Toungoo strafed Mae Hong Son facilities. 26

25 February 1942: IAF 1 Squadron made another reconnaissance run from Toungoo which overflew Mae Hong Son. 26

28 February 1942: IAF 1 Squadron strafed Mae Hong Son airstrip, destroying IJA radio facilities. 27

03 March 1942: Regarding the Allied air activities in February noted above, the implication of anything Japanese in the Mae Hong Son area through at least this date was probably premature.

Deployment maps from the Japanese official history of the war are available on-line, with translations on the Warbirds Forum website: 28

Air Units Deployment in Thailand and south Burma (23 Dec 1941)

The 5th Hiko Shidan deployment (22 Jan 1942)

South Burma Air Operations (mid-Feb 1942)

The 5th Hiko Shidan Deployment (03 Mar 1942)

None show Mae Hong Son.

A recent Japanese-language review of IJAAF operations in Burma 29 recounts the Allied version of 03-05 Feb 1942 events in Mae Hong Son, then observes:

. . . at that time, the 77th Sentai (Squadron) was 200 km SE at Lampang and the 31st Sentai was further away at Phitsanulok. 30

and finally comments:

Japanese records about these same air raids have not been found. 31

Regardless of the above review, the Mae Hong Son airstrip was located in Thai territory and Thailand had allied itself with Japan; thus the airstrip was a legitimate enemy target.

An explanation for presence of an aircraft in the Mae Hong Son hangar might lie in the original purpose of the airstrip: passenger and mail transport. Damage to a Thai civilian aircraft, particularly at a field not used by the IJAAF, would / could not have been reported by the IJAAF. Working against this interpretation are the other local memories of a bridge (somewhere around Mae Hong Son) having been bombed — but no recollection of a plane having been attacked on the ground.

Thailand’s Aerial Transport Co had seven Fairchild 24s and two De Havilland Puss Moths at the beginning of the war 32 and none functional at the end. 33 Only the demise of the last of the Transport Co aircraft is recorded in Steve Darke’s Thai Aviation History: Thai Air Accidents (Mar-45 entry), and that was associated with air service to Mae Hong Son. 34

Jagan Pillarisetti, a student of Indian Air Force history, comments:

I am of the opinion that the wartime reports were exaggerated. When things were not going well for the Allied campaign, there may have been pressure for intelligence agents to come up with ‘achievements’; so Majumdar may have blown up a building or a hangar, and someone put a spin on it and said an aircraft was inside. 35

To put this comment in perspective, recall that the British Commonwealth in Southeast Asia on 31 January 1942 was looking at Singapore under siege — the connecting causeway had just been cut, and Moulmein, Burma’s third largest city, 36 had just been abandoned to the Japanese who were obviously steamrollering towards Rangoon. 37 More revealingly was a United Press report relayed from Japan’s “Imperial Headquarters” that its taking Moulmein “virtually ended” use of the Burma Road over which the US had been providing supplies to the Chinese. 38 A 2012 biography of Air Marshal YV Malse, who participated in the early flights of Majumdar’s squadron, concluded: 39

The raid was a morale booster to the IAF squadron as well as for the other Allied units involved. The effort and the results were deemed important enough to be included in the regular daily dispatches sent to the US President FD Roosevelt by the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

Good news was desperately needed.

04 January 1943: The IJA’s Thai Occupation Army was established on this date, and three days later (07 Jan 1943) was put under the command of Southern Army Group. Sometime after, per direction of the Southern Army, the Occupation Army carried out “site investigations” to define various alternative potential routes for providing support for the IJA’s anticipated invasion of India. 40 One of those alternatives went through Mae Hong Son, which meant an IJA survey crew, possibly five or six men, would have passed through the town. They would probably have been accompanied by Thai soldiers acting as guides which might have screened the IJA presence. If noticed, their exposure to the local inhabitants would have been brief, and would probably have blended into the very visible and memorable project to construct the road which followed several months later.

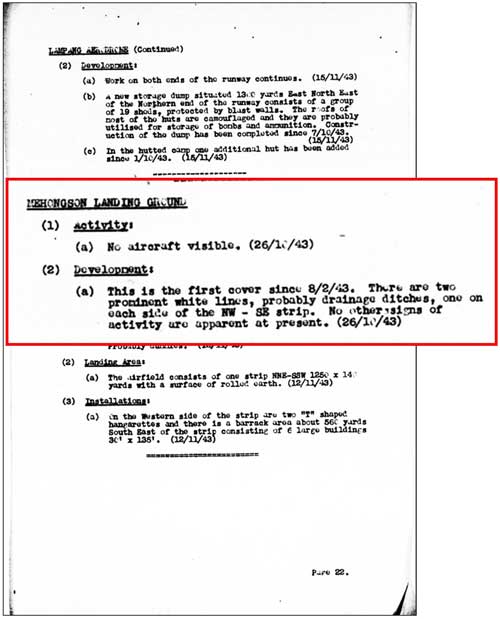

08 February 1943: An Allied aerial surveillance of Mae Hong Son airstrip was performed. That it had occurred was noted in Airfield Report No. 16 (November 1943), 41 more than eight months later; but the results are currently unknown because Airfield Reports for February and March, one of which might have contained the information, have not yet been made available by USAF Archives. 42 The location of the airstrip would have justified Allied surveillance because of its proximity to Burma; conversely, aside from a supply chain to Thailand being eroded by Allied attacks, the isolation of Mae Hong Son from Chiang Mai made development of its air facility unrealistic.

01 August 1943: IJA troops first appeared in quantity in the Mae Hong Son area sometime after this date as a part of building a road from Chiang Mai, Thailand to Toungoo, Burma.

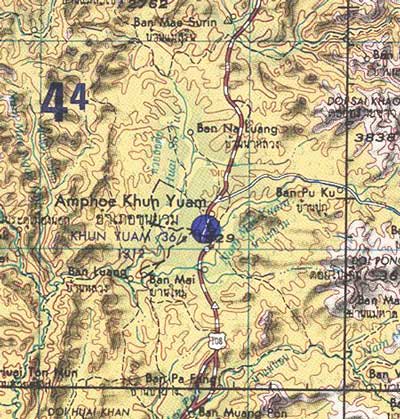

The official Japanese military history of WWII 43 records that, in preparation for the IJA invasion of India, a vehicle road was to be established connecting the railhead in Chiang Mai, Thailand, with the road, river, and rail 44 junction in Toungoo, Burma. That road was to pass through Mae Hong Son, and then through the border town of Khun Yuam in Thailand, and:

. . . Around 01 August 1943, 45 the IJA 15th Division’s [140th] Engineering Regiment and one Infantry Battalion, as well as the main force of the Independent 23rd Engineering Regiment [were assigned to build the road]. 46

Amongst local Thais interviewed long after the war, there was a consistent association of the appearance of Japanese soldiers with the construction of a road:

When Japanese soldiers came to build the roads . . . I used to see construction crews working on the road . . . supervised by one Japanese engineer. [Only] three or four months after the road was completed, thousands of Japanese soldiers began returning to Khun Yuam. 47

Two years before the Japanese defeat [ie, 1943], Japanese soldiers came to Ban Mae Surin. I would ask them where they were going. They told me that they would go to China. 48

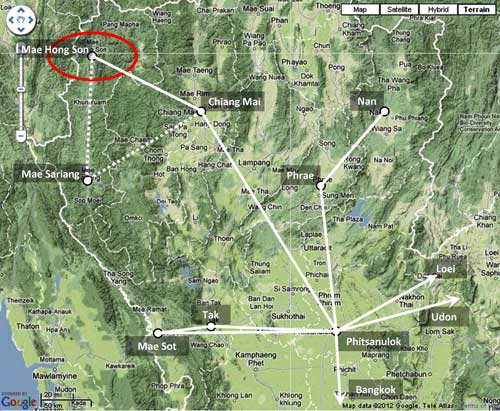

September 1943: Oddly, while the Survey of India labelling of the town in 1941 included Mae Hong Son (as well as Muae To), and US State Department documents had done similarly in 1940-1941, the USAAF (Army Air Force) Aeronautical Chart two years later called out neither the town name nor its airstrip. Its location is approximately as shown as a red dot on this extract from the chart: 49

26 October 1943: No aircraft were visible at the airstrip at this time, but possible improvements in site drainage were visible. Improvements at the airstrip would be consistent with the arrival of IJA troops building a road from Chiang Mai to Toungoo, Burma — and improving existing facilities in-between.

More interesting is that the site had not been checked since 08 Feb 1943, a lapse of more than eight months: this suggests that the Allies’ estimated potential of the airstrip for significant activity was low. 50

09 November 1943: The IJA road project linking Chiang Mai with Toungoo, Burma, via Mae Hong Son, was largely abandoned, because it was seen as impossible to complete in time to support the IJA invasion of India, which was planned to start four months later, on 06 March 1944. 51

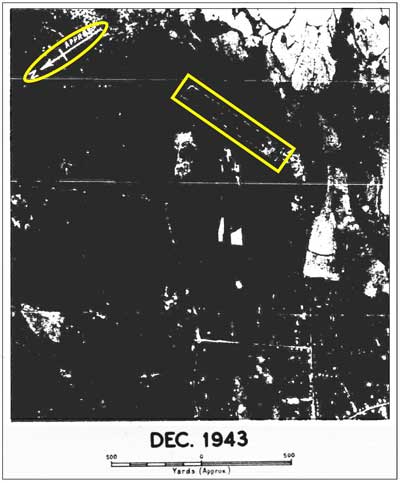

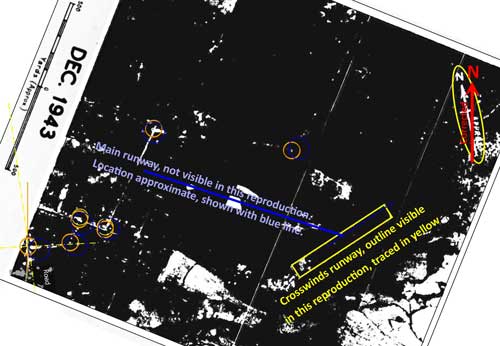

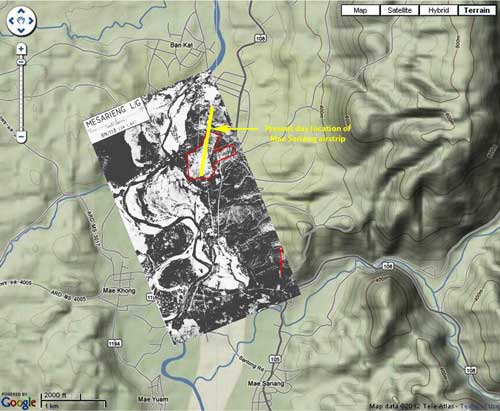

December 1943: An Allied intelligence report provides an aerial photo of Mae Hong Son airstrip; key features initially distinguishable are marked with yellow surrounds: 52

The above aerial photo is rotated below so that north points “up page”, per standard map convention: and both runways are defined as noted: 53

This realignment relies upon locating prominent features on different aerial photo sources and then matching them on overlays (hence the unlabeled small circles and lines). Note that the photo’s original north was designated “approx”. The quality of the photo is very poor because it is a microfilm copy of a printed publication, again, itself of unknown quality.

- รายงาน การ สําร จอขุดค้น ตาม โครงการ คึกษาเชิงอนรักษ์แหล่ง ฝังศพทหารญี่บุน – สมัย สงครามโลกครั้งที่ 2 จังหวัดแม่ฮ่องสอน – หัางหุ้นส่วนจํากัดเฌอ กรีน – เสนอต่อ – จังหวัดแม่ฮ่องสอน – สำนักงานโบราณคดีและพิพิธภณฑสถาน แห่งชาติที่6 ใชียงเหม่ (1999) Report on Archaeological Research for the Japanese Soldiers Burial Project World War II Era – Mae Hong Son Province (Chiang Mai: Green Tree, LLP, Ltd, submitted by/for Mae Hong Son Province Archaeology & National Museum Office 6, Chiang Mai, 1999), pp 80 & 118. Hereafter: Report on Archaeological Research.[↩]

- Report on Archaeological Research, p 117. While formative elements of the Free Thai movement did exist at this early date, it is very unlikely that they were able to mobilize aircraft, even if only for psychological support.[↩]

- Report on Archaeological Research, p 80.[↩]

- “Terrain” map from Nations Online; accessed 20 May 2012, but no longer available on-line. Overlay based on Airfield Report No. 32, Mar 1945, aerial photo “Mae Hong Son Landing Ground”, unnumbered page (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8056 p 53). Annotations by author using Microsoft Publisher.[↩]

- Per reminder from Mark Haselden on Warbird’s Forum page: Mae Hong Son attack, Jan 1942, 1739:55 01 Jun 2008.

In an unrelated incident in Nov 1943, but illustrative of the inaccuracies of bombing in that era, one bomb in the attack on Chiang Mai’s rail station was recorded as landing 800 m (2600 feet) from the target; that was a mid-altitude attack and many more landed past the target.

For an interesting discussion on factors in bombing accuracy, see paragraphs 5, 6, & 7 of Bombing Accuracy in a Combat Environment ((this page is supposedly active, but Maxwell AFB acknowledges not currently accessible for technical reasons[↩]

- Young, EM, Aerial Nationalism (Washington: Smithsonian, 1995), p 185; in reference to Foong Bin 32. What “enemy troops” were involved is not clear.[↩]

- ibid, pp 184-185[↩]

- Per Mark Haselden, ibid.[↩]

- Extract from map titled Burma, Geographical Section, General Staff No. 4280 (North Sheet) War Office 1942 (USAF Archive microfilm reel 8021 p 19).[↩]

- Airfield Report No. 21, Apr 1944, “Record of Airfield Activity & Development – Thailand”, unnumbered page (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 p645).[↩]

- Note that the detail of the crosswinds runway here appears almost identical on the previously referenced 05 February 1945 aerial photo, which is equally obscure, but is confirmed by the January 1944 miniature depiction of the airfield[↩]

- Pearson, Michael, Burma Air Campaign (Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Books, 2006), pp 36, 37.[↩]

- “Into Burma” in Air Marshal YV Malse: A Tiger Pilot Remembers by Jagan Pillarisetti[↩]

- as printed in The Racine Journal-Times, 10 Feb 1942, p 2.[↩]

- as printed in The Charleston Gazette, 19 Feb 1942, pp 1 & 4.[↩]

- Frances, Neil, Ketchil (Masterson NZ: Wairarapa Archive, 2005), p 76: also Shores, Christopher & Brian Cull, with Yasuho Izawa, Bloody Shambles vol II (London: Grub Street, 2000 reprint), p 259. Much more detail on Indian Air Force (IAF) action during this 03-05 Feb 1942 is available at: Air Marshal YV Malse: A Tiger Pilot Remembers by Jagan Pillarisetti). Note that these sources do not support a report that an aircraft in the hangar had also been destroyed.[↩]

- Pearson, ibid. Note that the aircraft in the hangar is not identified.[↩]

- Frances, ibid, p 76. Note that Bargh does not mention an aircraft in the hangar.[↩]

- Jagan Pillarisetti email 00:11 29 Jun 2008: flight logs of Pilot Officers Anantha Ananthanaryanan and Haider Raza. Unfortunately, as yet, no independent confirmation has been found for the hits.[↩]

- Young, ibid, p 185. The first contingent of the 50th Sentai did not arrive in Chiang Mai until 18 Feb 1942 per South Burma Air Operations.[↩]

- wireless station: the latter might possibly have existed (reports are definitely mixed about it):

a. if powered by a standalone generator, but otherwise power generation did not come to Mae Hong Son until January 1953 (Boonserm Satrabhaya, Chiang Mai and the Aerial War (Bangkok: Saitharn Publication House, 2003) p 138);

b. further, there were only radio transmitters at Don Muang, Phitsanulok, Korat, Udorn, and Bandon airfields in 1941/2 (Airport Directory South East Asia (Washington: USAAF 28 June 1942), p III). The IJA might have installed a radio with generator, except that the lack of traffic at the airstrip would not likely have justified the expense;

c. communication between Mae Hong Son through Chiang Mai to points south, and also continuing further north to Pai, was available via a telegraph system established sometime before 1915 and probably powered by batteries charged by hand-cranked generators in the more distant stations (telegraph lines are shown on a Monthon map dated 1915 in History of Lan Na, p 184: Map 13, Ministry of Education, Phumisat Prathet Sayam, pp 156-157) [↩] - From RIAF official history sources, per Jagan Pillarisetti email 10:44 21 Jun 2008: information cited in The Official History of the Royal Indian Air Force 1933-1945 (Ministry of Defence, India, 1961); but see Jagan Pillarisetti‘s comment below.[↩]

- “Toungoo Airdrome Bombed”, The New York Times, 05 Feb 1942, no page cited in on-line archive.[↩]

- ibid[↩]

- Per Jagan Pillarisetti email 10:44 21 Jun 2012: flight log of Pilot Officer Haider Raza (later Air Vice Marshal of the Pakistan Air Force).[↩]

- ibid.[↩][↩][↩]

- Per Jagan Pillarisetti email of 00:11 29 Jun 2008: information cited in The Official History of the Royal Indian Air Force 1933-1945 (Ministry of Defence, India, 1961). Again, any reference to IJA presence at this early date was probably premature. For perspective, see Jagan Pillarisetti‘s comment below.[↩]

- Warbird Forum links are as shown. Maps are from:

戦史叢書 (東京: 防衛庁防衛研修所戦史室, 南方進攻陸軍航空作戦 (編集), 1970年)

Senshi Sosho (War History Series) vol 34 (IJAAF’s Drive to South Pacific Area) (Tokyo: Asagumo Shimbunsha, 1970), pp 338, 583, 597, 607.[↩] - 装丁寺山祐策, ビルマ航空戦・上 (東京: 本印刷株式会社, 2002),

Umemoto, Hiroshi, Air War in Burma (Tokyo: Dai Nippon, 2002).[↩] - ibid, p 64.[↩]

- ibid. “この空襲に相当する日本側の記録は発見できなかった。”[↩]

- Young, ibid, p 102.[↩]

- Young, ibid, p 216.[↩]

- See entry for 20 Mar 1945.[↩]

- Jagan Pillarisetti email of 10:29 01 Jul 2012. A brief biography of Majumdar is available at Wing Commander Karun Krishna Majumdar.[↩]

- The United Press, 02 Feb 1942, in “RAF Blasts Foe in Boats in Burma”, The New York Times, 02 Feb 1942, no page number cited in archive.[↩]

- Oakland Tribune, 31 Jan 1942, p 1.[↩]

- The New York Times, 03 Feb 1942, no page number cited in archive. But according to The United Press, quoted in “Fliers Smash Japanese in Burma . . .”, The New York Times, 05 Feb 1942, no page number cited, this assessment was a bit premature: this goal was still perhaps 90 miles (144 km) beyond.[↩]

- Jagan Pillarisetti, A Tiger Pilot Remembers-Air Marshal YV Malse, 2012 (a very interesting account in itself) [↩]

- 戦史叢書 : Vol 15: インパール作戦―ビルマの防衛 (東京: 防衛庁防衛研修所戦史室 (編集), 1968年). Senshi Sosho, v 15: Imphal maneuvers – Burmese defense (Tokyo: Asagumo, 1968), [hereafter, Senshi Sosho v15] p 139.[↩]

- Airfield Report No. 16, Nov 1943, p 22 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 p 277).[↩]

- Query sent by email 18:13 17 Jun 2012: no response as of 26 Jun 2012.[↩]

- 戦史叢書)Senshi Sosho (War History Series) [↩]

- By this time, however, one of the two sets of railroad tracks had been “taken up” per Brown, Atholl Sutherland, Silently into the Midst of Things (Victoria BC: Trafford, 2001), p 40. [↩]

- This date is generally confirmed by a statement later in the Senshi Sosho text: “The Army Group, on 12 August 1943, gave the order to prepare for the Imphal operation to the 15th Army” (Senshi Sosho v15, p 148).[↩]

- Senshi Sosho v15, p 139. [↩]

- บ้อมูลเส้นทางเดินทัพทหารญี่ปุ่นในอำเภอบุนยวม สงครามมหาเอเชียบูรพา (สงครามโลกครั้งที2) จดทำโดยพันตำรวจโท เชิดชาย ชมธวัช, [Chomtawat, Cherdchay, Information about Japanese soldiers traveling through Amphur Khun Yuam in World War 2 [15 Interviews] (self published, undated, but before 2004)], (hereinafter, Information about Japanese Soldiers), unpaginated, Mr Woriya Opra (Interviewee No 1).[↩]

- ibid, Mr Boon-ton Sriwichai (Interviewee No. 8).[↩]

- Extract from McMaster U Digital Archive, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; My ref: _MAPS\THAILAND Maps\COLLECTN McMASTER\677-macrepo_76844.jpg. I haven’t been able to find a copy of the previous map to see how the town had been labelled.[↩]

- Airfield Report No. 16, ibid.[↩]

- Senshi Sosho v15, p 179.[↩]

- Airfield Report No. 21, Apr 1944, unnumbered page (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 p645) (note that, for whatever reason — perhaps targets of higher priority, it took six months for the photo to be published).[↩]

- ibid. Realignment based on Google Earth view of the airstrip area plus contents of Airfield Report No. 32, Mar 1945, aerial photo “Mae Hong Son Landing Ground”, unnumbered page (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8056 p 53).[↩]