Wat Phra Yuen: Crash site of Jack Newkirk, Flying Tiger Ace

Wat Phra Yuen, (Google Maps link)1 just east of Lamphun Town, was notable in WW2 for having witnessed the fiery death of Flying Tiger2 Ace “Scarsdale Jack” Newkirk3 in the crash of his P-40 on the morning of 24 March 1942.

Numerous accounts of the death of Jack Newkirk, Flying Tiger Ace, have been written over the years. Two particularly useful versions of his crash appear in a 2009 exchange on Dan Ford’s Warbird’s Forum. As products of distillation offered by the passage of almost 70 years, hopefully they provide the most up-to-date and accurate information.

Dan first presented Jack Eisner’s findings in Feb 2009:

Jack Newkirk, the view from the ground (Jack Eisner) (offsite link)

Photo-map of the crash site (Jack Eisner) (offsite link)

Then, in Apr 2009, Dan published a response from Bob Bergin:4

Jack Newkirk, was he shot down? (offsite link), which includes excerpts from Bergin’s: Aviation History article, “Flying Tiger, Burning Bright”, July 20085

On the face of it, Jack Eisner’s position seems to make more sense:

Bob Bergin acknowledges the eyewitness accounts on the ground which conflict with pilots’ records about Newkirk’s crash — actually, per his account, Bergin learned of the views from the ground in 1994 as a part of a Flying Tiger reunion in Chiang Mai. However, he only published that information in 2008 with his Aviation History article; and Eisner did not learn of it and get a copy until late Dec 2008. While its absence resulted in some duplication of effort by Eisner, it was useful in that it forced Eisner to independently confirm — and interpret — the testimony of (now) very elderly residents about the crash. While details do differ in the two reconstructions, it is more the tenor of Bergin’s article which favors the pilots’ accounts of the crash over those of the people on the ground that should catch a reader’s eye, and his seeming effort to discourage further research. Bergin begins his last section with:

So what did happen to Jack Newkirk . . . at this point who can say, and I don’t think it’s fair to make that judgment now.6

Perhaps Bergin is implying that it could be disrespectful to the memory of Jack Newkirk to continue research that might point to a human flaw in a “legendary American hero”. Such an attitude does, however, rather fly in the face of the concept of the orderly development of knowledge. In actual fact, such an attitude is foreign to the philosophy of the study of history:

The body of literature on almost any historical subject takes the form of an ongoing debate.7

Thus I think we are obligated to offer an alternate, informed, reasoned judgment after the event.

This is not intended to belittle the Flying Tigers’ courage and capabilities in any way, but it is important to recognize that all the pilots were operating in a combat mode, under extreme stress. They had already made strafing runs on actual ground targets by the time they got to the area where Newkirk would crash. They were at that site for mere seconds and the actual circumstances leading to Newkirk’s crash were not witnessed by any of them. The event was one of many on that flight, and that flight was one of many in which they had already participated. In this particular instance, the pilots’ recollections were necessarily largely speculative. They needed to make sense of what had happened for their flight reports, but they were working with inadequate information.

Conversely, on the ground were a number of basically neutral observers, who were there for the whole of the sequence of events. Not only did they witness events surrounding the crash, they were there to see and possibly to participate in the subsequent cleanup. It was probably the closest any got to WWII combat (which was in contrast with the serious air attacks on Chiang Mai,8. This single war-related event at Lamphun would have left a vivid impression on residents there.

I think it more logical to envision Newkirk, having been fired on by an anti-aircraft (AA) battery at the Ban Tha Lo railroad bridge, proceed to circle to make a run on the bridge to return fire and neutralize the AA battery. He would have planned to approach the AA battery as low as possible in order to get below the vertical range of those guns. During that run, as he was completing his turn to line up on the bridge, he was distracted by a “target of opportunity”, just momentarily, but long enough so that he could not react in time to avoid a flame tree — if he even saw it at all.9

Events happen ever so quickly at 300+ mph (~500 kph). That’s 440 feet per sec, a mile every 12 seconds (134 meters per sec, a kilometer every 8 seconds). Already at low altitude, diving further to treetop level. A distraction of only seconds. And during that distraction, a tree suddenly appeared in the flight path. The version of events that Jack Eisner suggests is quite plausible. And quite simple: Occam’s razor10 applies.

New facets

RTAF Lamphun Airstrip location

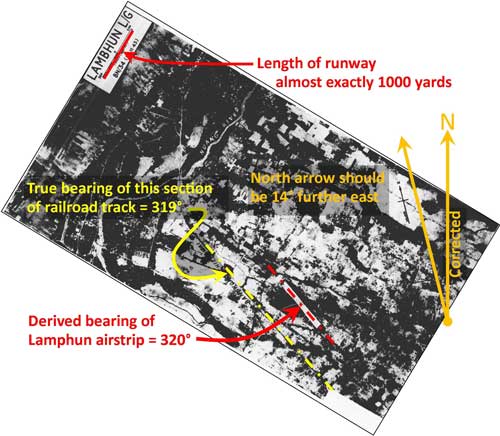

Subsequent to the postings in the Warbirds’ Forum and the above review, more detail has surfaced with regard to circumstances surrounding Newkirk’s fatal crash. Per an aerial photo in an Allied intelligence report (here annotated):11

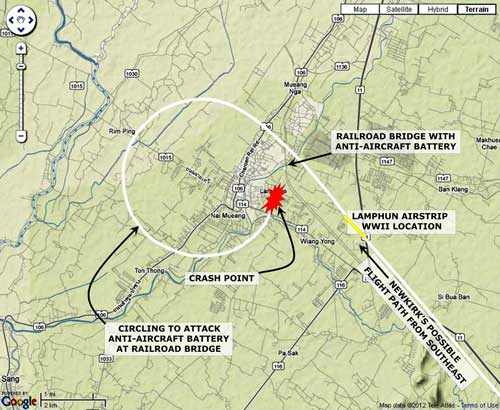

. . . a Royal Thai Air Force (RTAF) military airfield, the only airstrip recorded in the immediate Lamphun area during WWII, can be accurately located, and Jack Newkirk’s flight path leading to his crash point more closely roughed in:12

The airstrip — existing at the time of Newkirk’s fatal crash — could be seen to neatly jibe with Thai recollections of:

- A plane approaching from the southeast (to strafe the airstrip), and then

- circling Lamphun (to strafe the AA installation at the bridge) before crashing at Wat Phra Yuen.

In addition, RTAF history confirms that the airstrip at Lamphun was attacked on the morning that Newkirk crashed:

On 24 March 1942, enemy Tomahawks bombed . . . Lamphun airport around 0700 hours. . . 13

More information may lie in Royal Thai Army records: the Thai Phayap Army’s 35th Infantry Battalion had responsibility for protecting the rail line between Lampang and Chiang Mai at that time.14

Disposition of Newkirk’s P-4015

The wreckage of Newkirk’s aircraft was collected in front of the Lamphun Police Station where it was photographed, with the Nationalist Chinese roundel prominent:16

Subsequently it was moved to the IJAF headquarters building in the occupied Wattanothaipayap School. From there it was sent to Bangkok by rail with no further record available.

A rumor that the wreckage was at some point put on display at Yupparaj School has proven untrue: after the war, the RTAF donated an old Allied aircraft for that rumored display which was near the southeast corner of the school property at the intersection of Ratwithi and Ratchaphakinai. The display, similar in appearance to those of aircraft around the Chiang Mai Airport today, was vandalized and pieces scavenged until the aircraft eventually disappeared.17 It was whole in 1980.18

| First published on Internet | ||

| Added excerpts from The Art of Strafing and Motion Induced Blindness | ||

| Added section: “New Facets” | ||

| 3 | 2013 Apr 15 | Minor corrections; added ref to time of Lamphun attack. |

| 4 | 2024 Feb 29 | Converted to WordPress by Ally Taylor |

| 5 | 2025 Mar 29 | Updated, author errors & typos corrected |

Last Updated on 25 February 2026

- Google Earth. N18°34.565 E99°01.185. Map extracted from: แผนที่ทางหลวงประเทสไทย (กรุงเทพมหานคร:กรมทางหลวง, 2009) [Road Map of Thailand (Bangkok: Department of Public Highways, 2009)] , p 88. Annotations by author using Microsoft Publisher.[↩]

- Flying Tigers, or more properly, the American Volunteer Group (AVG). Dan Ford offers an excellent history in Ford, Daniel, Flying Tigers: Claire Chennault and his American Volunteers, 1941-1942 (New York: HarperCollins / Smithsonian Books, 2007).[↩]

- John Van Kuren Newkirk (15 Oct 1913 – 24 Mar 1942).[↩]

- Dan Ford added an introduction on his website when he published Bob Bergin’s response: Jack Newkirk, down in Thailand (Dan Ford).[↩]

- Bergin, Bob, “Flying Tiger, Burning Bright”, Aviation History, July 2008, pp 24-31.[↩]

- Bergin, Bob, Jack Newkirk, was he shot down? (offsite link) Link revised per Dan Ford “New & improved for August” email, 1924 hrs 01 Aug 2014.[↩]

- Gilderhus, Mark T, History and Historians: A Historiographical Introduction (Upper Saddle River NJ: Pearson / Prentice-Hall, 2007) p 86.[↩]

- Amongst others, a USAAF air raid on 21 Dec 1943, targeting the railroad station at Chiang Mai, 22 km to the north, and killing 300+.((บุญเสิม สาตราภัย, เชียงใหม่กับภัยทางอากาศ (Satrabhaya, Boonserm, Chiang Mai and the Aerial War (Bangkok: Saitharn Publication House, 2003), p 23.[↩]

- An alternate possibly contributing factor might have been “target fixation” or “channelized attention”. See Lewis, Richard, “The Art of Strafing” (offsite link) in Airforce Magazine, July 2007, esp paragraphs 11-13, which start “For most fighter pilots . . .”. While the article deals specifically with the A-10 “Warthog”, the same principles would apply to strafing with a P-40. Another phenomenon which might have figured into Newkirk’s crash was Motion-Induced Blindness (offsite link) by Terry Keller in a Premier Flight Center document.[↩]

- A principle urging one to select among competing hypotheses that which makes the fewest assumptions and thereby offers the simplest explanation of the effect. (A principle urging one to select among competing hypotheses that which makes the fewest assumptions and thereby offers the simplest explanation of the effect. (per Wikipedia Occam’s razor (offsite link), accessed 02 May 2012).[↩]

- (Airfield Report No 21, Apr 1944, unnumbered page (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 p 657). For further discussion about this aerial photo, see Lamphun Airstrip.[↩]

- “Terrain” map from Nations Online Project: Searchable Map and Satellite View of Thailand using Google Earth Data (link no longer available). Annotations by author using Microsoft Publisher. The diameter of the flight circle is about 5 km (3 mi).[↩]

- ประวัติกองทัพอากาศไทย ในสงครามมหาเอชียบูรพา พ.ศ. ๒๔๗๔ ๑๔๗๗ (กองทัพอากาศ: กองทัพอากาศไทย, พ.ศ. ๒๕๒๕) Royal Thai Air Force History in World War II 1941-1945 (Bangkok: Royal Thai Air Force, 1982), p 93.[↩]

- ประวัติศาสตร์การสงครามของไทย ในสงครามมหาเอเชียขูรพา (กรมยุทธศึกษาทหาร กองบัญชาการทหารสูงสุด พ.ศ.๒๕๔๐)

[History of the Royal Thai Army during World War II (Bangkok?: RTA Command School, 1997)], p 125. I was reminded of this after Jack Eisner mentioned it in his 24 Mar 2013 Bangkok Post article, “Last Flying Tiger Remembered” (offsite link).[↩] - Item added 29 Nov 2013.[↩]

- photo provided by Sakpinit Promthep[↩]

- บำยประสัทรั่ แสบไชย, Prasit Sanchai, and วิจิตร ไอสุวรรณ, Witchit Isuwan, both retired from Wattanothaipayap School. Discussion at my house, 13 Dec 2009.[↩]

- คุณ หลิน เขียวผิว, Lin Kaewphiw, my wife. Numerous discussions at our house.[↩]