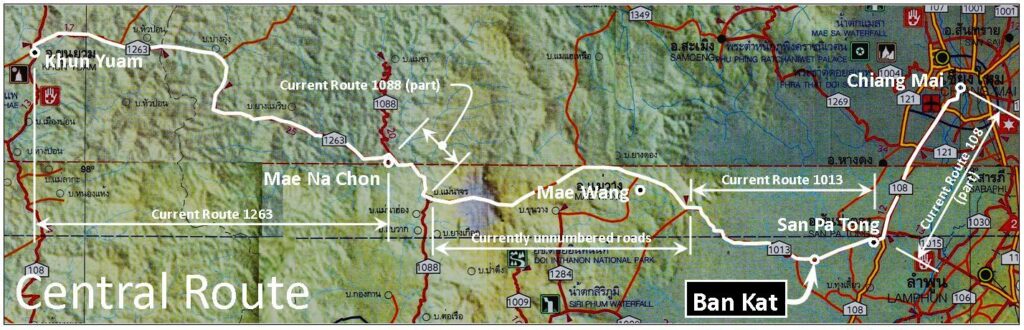

The Central Route was one of three serving Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) troops retreating from their failed invasion of India. The route went thru Ban Kat, site of an IJA clinic. The largest monument to the IJA in the north of Thailand was later established there.1

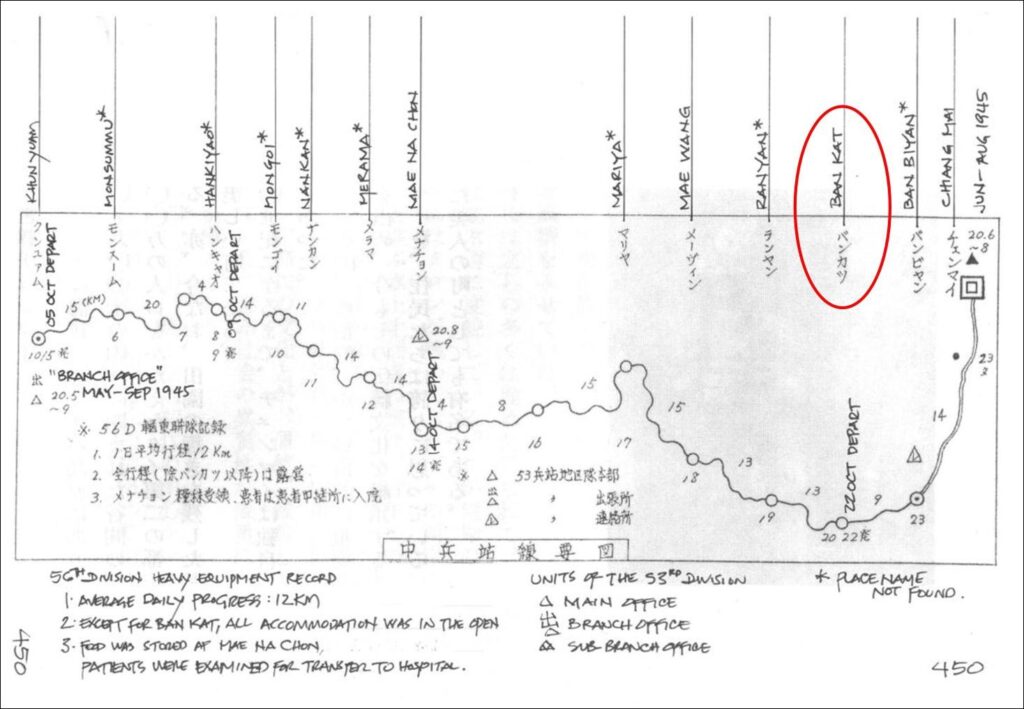

Following the IJA’s failure to invade India with its defeats at the Battles of Imphal and Kohima, a “Central Route”2 became one of three major arteries in Thailand for IJA troops retreating from Burma. Ban Kat3 was the second major stop on the route running easterly through Thailand from Khun Yuam to, first Mae Na Chon, then Ban Kat, and finally San Patong and Chiang Mai. Limited medical facilities were available at Ban Kat and, a few kilometers to the east, vehicles could pick up personnel for the trip to Chiang Mai. IJA personnel typically took 22 days to traverse the 160 km to Ban Kat. Wat Muen San in Chiang Mai was another 30 km beyond.4

Relevant chronology for Ban Kat follows:

1890s (BE2430s)

Teacher-monk Zaotamutein established Wat San Khayom5 in an area just north of present day Ban Kat; the site included a water well.6

1913 (BE2456)

At Zaotamutein’s death, the wat and its well were abandoned. 7

Following abandonment of the wat, Thai highway bandits who robbed and killed travelers, dumped bodies of their victims down the abandoned well at the old Wat San Khayom. In addition, the well became a favorite dump site for bodies resulting from local drug wars (which existed even back then); nationalities in this activity came to include not only Thais, but also Burmese and Jin Haw Chinese. Over time, a number of bodies accumulated; this, coupled with no maintenance, eventually filled the well in above the water table and it went dry.8

1941-1945 (BE 2484-2488)

There are three primary sources for information about activities at Ban Kat during the period when the IJA was present.

There are three primary sources for information about activities at Ban Kat during the period when the IJA was present.

It must be noted that access to all three was only possible through the gracious assistance and guidance of Konishi Makoto, manager of the Japanese War Memorial at Ban Kat.9

SOURCE 1. Two sisters, Komloo and Yai Yin,10 then 15 and 18, who continued as residents of Ban Kat, were present when portions of the IJA, defeated at Imphal and Kohima, India, retreated via the “Central Route” which goes through the town.11 With parents emigrated from Burma, the sisters’ first language had been Burmese which was later supplanted by Tai Yai. They grew up in a house on a lot along Bat Kat Soi 4/612 which is now occupied by Komloo’s house and shop.13

Sisters Kamloo & Yai Yin, with able interpreter, Wiyada ‘Noi’ Kantarod, at Wat Chamlong where they were interviewed.14A significant number of Ban Kat residents at that time were relocated Burmese. They congregated in the south of the town. The two active wats in that part of town, Chamlong and Umpharam, were manned by Burmese monks. Another wat — long abandoned — was Wat Maan, or Wat Muan To near the center of the town; the latter means “Burmese wat” in Burmese. The sisters maintain that a British administrative type was present in the village before the war to oversee interests of the Burmese there. They believed him to be a representative of the British colonial government in Burma; however, he would more likely have been an employee of one of the British logging companies.15

In 1945, the sisters sold vegetables and noodles to Japanese soldiers at the local market which was located at the east end of their soi.16 Soldiers used rice17 and salt to barter for market goods; they did not have any medicines to trade (as some had been able to do in Khun Yuam). The soldiers would combine everything they bought in large kettles, cook it up, and then dole it out with rice container lids.

There was a lamyai plantation where the local market is today, directly across the street from Komloo’s house. At that time, the street was just a dirt path.

The general alignment of the main road serving Ban Kat, with connections immediately east and west, was the base for Thai Route 1013 today.

The first time Yai Yin saw any Japanese was in 1945 when soldiers were returning from Burma. Neither sister recalls any Japanese ever having passed through the town previously: at the least, this would have been an IJA scouting crew evaluating the suitability of the road through the town for supporting the Japanese invasion of India.18

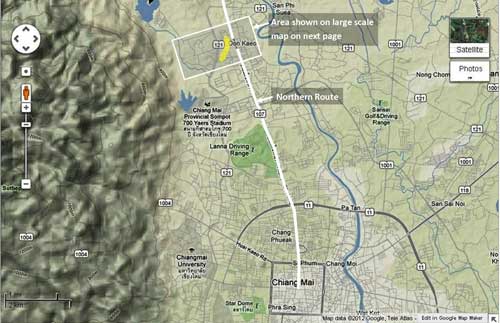

Satellite view of Ban Kat area19 (circled numbers refer to text following the map):

From Khun Yuam (see map at top of page), 99 km west of Ban Kat,20 a few high-ranking officers rode in on horses;21 but most soldiers walked. No one came by motor vehicle: “roads” were, in most instances, nothing more than paths. Vehicle fuel was simply not available between Kemapyu in Burma and Ban Kat: some vehicles by virtue of fuel siphoned from stalled vehicles managed to get as far as the Khun Yuam area.22 For transport just in the Khun Yuam vicinity, some vehicles had been converted to steam, fueled by wood or coal.23 From Khun Yuam, Japanese soldiers arriving at Ban Kat would have last passed through Mae Na Chon (west of Map Point 1).24 There was no mention of self-powered vehicles operating in Ban Kat. This was the result of the path to Chiang Mai crossing the Nam Mae Khan (the Khan stream), at Map Point 7, about three kilometers east of Ban Kat: the unbridged stream was an effective barrier to motor vehicles.

Coming into Ban Kat (Map Point 2), soldiers were to report to Wat Maan25 for medical evaluation and then assignment to quarters.

The ruins of Wat Maan (Map Point 3) were visible during our visit in 2008 through the heavy foliage:

More recently, vegetation obscuring the building has been cut back revealing its true extent and more likely appearance 80 years ago:

Because of their large numbers, however, control was difficult and some soldiers never “reported in”, but just wandered into the various living facilities. Soldiers stayed not only at the wats, but also in innumerable tents scattered throughout the Ban Kat area. Some troops were sent 1.6 km north to the ruins of Wat San Khayom,30 though the ruins themselves would have provided no shelter:

Wat San Khayom today, probably much as it appeared in 1945 (Map Point 3)31

More typically, soldiers wandering into Ban Kat, went on past Wat Maan and Komloo’s house/store, Map Point 413, and turned south to Wats Chamlong, Map Point 5,32 and Umphara, Map Point 6,33 to overnight.Both Wat Chamlong and Wat Umpharam survive and prosper today:

Wat Chamlong34 Wat Umpharam35

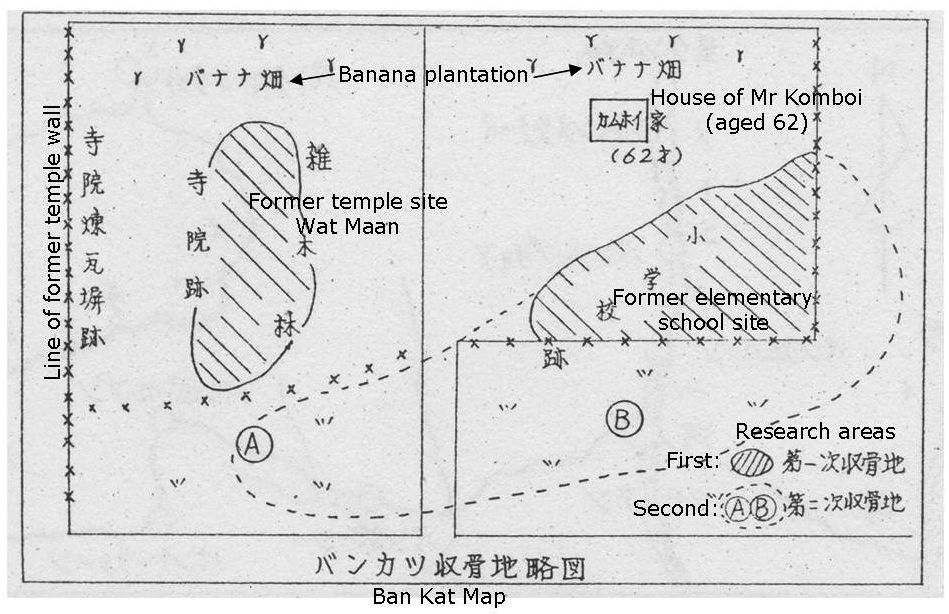

There were no civilian medical facilities in Ban Kat, and apparently only a very rudimentary clinic set up by the IJA at the ruin of Wat Maan: Soldiers who died around Ban Kat were buried on the grounds of Wat Maan; which extended to include the current residence of a Mr Kamboi. See map sketch below:Map of burial area at Wat Maan in Ban Kat36

Very little is known about Wat Maan, earlier rendered as Wat Muai To,37 other than the name means ‘Burma’ in both the Tai Yai and Burmese languages; this refers to the nationality of the monks who established it. Superstitious local residents avoid the area for all the potential spirits that might reside there. Mr Komboi is apparently not superstitious.Because a stream, the Mae Nam Khan, cut across the road to Chiang Mai about three kilometers east out of the town, motor vehicle transport only began from that point38 on to Chiang Mai with its better medical facilities.

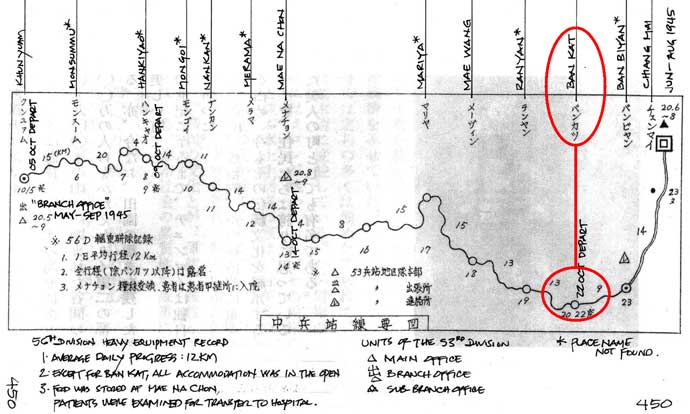

SOURCE 2. Japanese war veterans organized an effort to recover IJA remains in Thailand, Burma, and India which got underway in 1977. The highlights of their efforts were published,39 but there is little information about conditions at Ban Kat. It was located on the Central Route, for which the following map was provided:40

What was presented were these observations:

Patients / walking wounded were sent via the northern route because it was believed to have fewer steep slopes and there was a greater number of way point stations than the very mountainous (but shorter) central route. . . . For those in fairly good physical condition, the central route was a reasonable alternative . . . . 41

Those IJA troops following the Central Route first passed through Mae Na Chon, where the village chief during the war recalled these details which were generally relevant to Ban Kat, 68 kilometers further east:

1) Japanese soldiers who had come were relatively healthy, and they had rested at this village for a few days before heading off on the eastern mountain road toward Chiang Mai. . . .

6) Near the end of the war, on average once a week, a group of soldiers would pass by on its way to Chiang Mai.42SOURCE 3. The Etou Foundation (慧燈財団), in an early comment, reported:

In the final stages of the war in 1945, the Japanese military withdrew from Burma and returned through this area. When many died of malaria and related illnesses, their comrades buried them in the abandoned well at the San Khayom temple.43

This statement, however, appears to have been in error. As noted above, the sisters remember things differently: Soldiers who died around Ban Kat were originally buried on the grounds of Wat Maan, with remains disinterred years later when portions of remains were sought to return to Japan, in accordance with Japanese custom.44 Only then were the rest of the remains put down the well. And, as has been noted, prior to the war,45 the well had been used for disposal of local bodies.

Curiously, there does not appear to be any Thai research published about this location.

Nov 1977 (BE 2520)

Partially supported by a Japanese Government financial grant, Japanese war veterans came to Ban Kat asking where the Japanese army had stayed and where the dead had been buried. They were directed to Wat Maan. Neither Wat San Khayom nor its well are mentioned in the final report of that effort.46

Jan – Mar 1978 (BE 2521)

The results of on-site research by the veterans were followed up by younger Japanese who retrieved what remains could be found, which eventually numbered 63.47

Portions of remains recovered were cremated with proper Buddhist ceremony and the ashes returned to Japan:48 the rest of the remains were relocated from the Wat Maan burial ground to the well at Wat San Khayom.

However,

. . . the cultural importance to every Japanese of returning some portion of a dead comrade’s body to his home.49

would have guided the Japanese in handling the remains: a small portion of each would have been retained for proper ceremony and return to Japan, with the rest of the remains committed to the care of the well.

1989 (BE 2532)

Shirabe Kanga was one of several Buddhist monks who had gone to Cambodia to help refugees. On the way back, they met relatives of Japanese war dead from Saga Prefecture (located on the northwest coast of Kyushu, Japan’s southernmost main island), and went with them to Chiang Mai. In Chiang Mai at Wat Muen San, they met an old Thai monk who urged them to recover the remains of IJA troops

The new Witayacom High School serving Ban Kat was commissioned.50 During construction, the well was rediscovered along with its bones which had come from both local mayhem as well as the subsequent relocation of IJA remains.

1990 (BE 2533)

Shirabe Kanga, motivated by the Thai monk’s urging, began the search for IJA remains.51

1992 (BE 2535)

Per an Etou Foundation information leaflet about the memorial (as translated):

. . . a team from Japan started searching in this general area for the remains of Japanese soldiers from World War II. As a result, the remains were discovered at Wat San Khayom’s abandoned well, in addition to other areas. The well was located on the grounds of the current Ban Kat Witayacom High School.52

1993 (BE 2536)

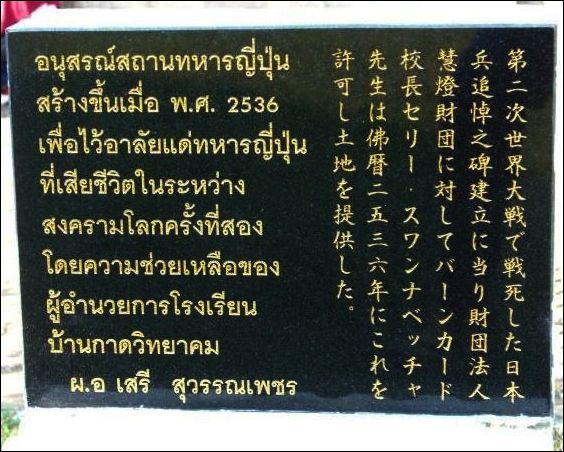

The Japanese found the location of the well attractive: it was remote from the development in Bat Kat in an appropriately quiet, peaceful area. An Etou Foundation English-language information leaflet about the memorial notes:

. . . the executive director of Etou Foundation, Shirabe Kanga, a Japanese monk, along with the Japanese Consul General in Chiang Mai at that time, visited the high school, seeking permission to erect a stone monument to the soldiers lost in the Thai-Burma Campaign [over the well].

Seri Swanapet, the school principal (1990-1997), and responsible for the water well, gave permission for the foundation to occupy the site because of the presence of the remains of Japanese soldiers.53

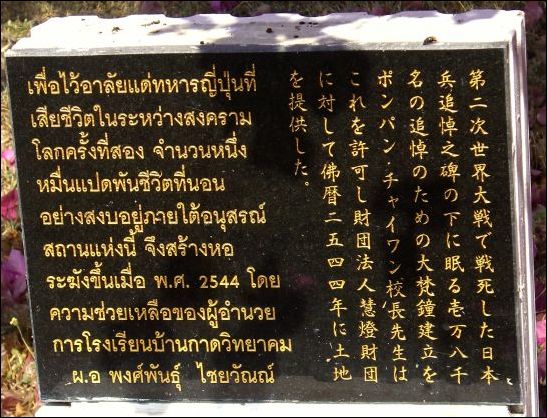

A bilingual Japanese-Thai sign at the entry point to the memorial area54

In 1993, the principal of Ban Kat High School offered a plot of land to the Etou Foundation to build a monument to Japanese military personnel who died in World War II.55

1995 (BE2537)Etou Foundation was formally established by Shirabe Kanga to facilitate the collection of remains and the building of a memorial. An educational assistance / scholarship program was begun in the Ban Kat schools.56

2001 (BE 2544)

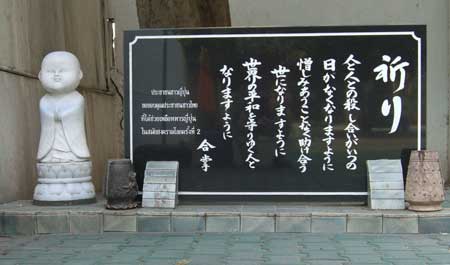

A pedestal on the left side of the bell tower written in both Japanese and Thai57

In 2001, the principal of Ban Kat High School gave permission to the Etou Foundation for construction of a bell tower in memory of Japanese military personnel who died in World War II.58

Etou Foundation website information about the memorial tells in translation that the bell and tower were constructed in 2002.

The 2011 ceremony was covered in detail on the Japanese language webpage, Etou Foundation News,59

However, there have been no entries since Feb 2012.

Date: Ongoing

Organized by the Etou Foundation, Remembrance Day Services are held annually at the memorial:60

Next: A tour of the Ban Kat Memorial Site

Revision List Rev Date Description 0 2010 Jun 11 Published on Internet using Dreamweaver 1 2024 Feb 29 Converted to WordPress by Ally Taylor 2 2025 Mar 27 Updated, author errors & typos corrected

- Map is composite from แผนที่ทางหลวงประเทศไทย Scale 1:1,500,000 (กรุงเทพมหานคร:กรมทางหลวง, 2009) [Road Map of Thailand, Scale 1:1,500,000 (Bangkok: Department of Public Highways, 2009)] of pp 2 & 4. Annotations by author using Microsoft Publisher. Routes used by IJA forces are here assumed to approximate currently existing roads. For reference purposes, the route is here described using modern highway designations where applicable. From Toungoo in Burma on Burma Route 5 past Mawchi to Kemapyu; across the Salween River and onto trails not later improved into Thailand to Huai Tonnun (บ้านห้วยต้นนุ่น); from there on improved, unnumbered roads to Pratumuang (บ้านประตูเมือง); then via Thai Route 1337 to Khun Yuam (ขุนยวม); then on Thai Route 1263 to Mae Na Chon (แม่นาจร); continuing on improved, unnumbered roads to Mae Wang (แม่วาง); then on Thai Route 1013 through Ban Kat to San Pa Tong (สันป่าตอง); and finally north on Thai Route 108 to Chiang Mai.[↩]

- The basis for the Central Route is not clear; the Japanese military history notes a decision to develop only a road roughly following the current Thai Route 1095 in support of its invasion of India (戦史叢書 Vol 15:インパール作戦―ビルマの防衛 (東京: 防衛庁防衛研修所戦史室 (編集), 1968年)[Senshi Sosho, vol 15: Imphal Maneuvers, Burma Defense (Tokyo: Defence Agency, National Defense College Military History Room, 1968)] (hereinafter “SS15“), p 140).[↩]

- บ้านกาด, ie, Ban Kat, is the Royal Thai Survey Department (RTSD) place name. It is also rendered in English as Ban Kad, Ban Gat[↩]

- 160 km is derived from map in SOURCE 2 below. The 30 km comes from the 9+14 distances shown on that map which seem to end at Hang Dong (unnamed) plus a Google Earth path plot of approximately 7 km (Hang Dong to Chiang Mai’s Silver Wat.kml).[↩]

- N18°36.530 E93°48.770[↩]

- “Details about the Monument Dedicated to Those Left Behind in the Thai-Burma Theatre”, Etou Foundation handout (undated, translated from Japanese).[↩]

- ibid[↩]

- Interview with Komloo and Yai Yin, lifelong residents of Ban Kat: with Kamloo on 29 Sep 2008 and with the two on 04 Oct 2009. Wiyada ‘Noi’ Kantarod was translator for both interviews. See below.[↩]

- In Thailand, Konishi Makoto (小西 誠) was a Japanese language teacher at the Ban Kat school. In that position, he became well acquainted with the unique historical content of Ban Kat relative to Japan and WWII. While maintaining his connections with the school, he took on responsibilities as manager of the Japanese War Memorial there. Since then, Konishi Makoto has resigned his teaching position, trained a replacement for his manager function, and resigned that function as well, to further his education in Japan. He, in turn, had been ‘discovered’ by Junko Kobata (コバタ ジュンコ), my first Japanese language tutor, who took an active interest in researching the history of the IJA in northern Thailand for this project. Author photo: CIMG3668a.jpg, 12 Sep 2008[↩]

- Family name missing.[↩]

- See map at top of page[↩]

- Ban Kat Soi 4/6 in Tambon Mae Wang (บัานกาด ซอย 4/6 เทศบาลตำบลแม่วาง).[↩]

- N18°35.865 E98°49.195[↩][↩]

- Author photo: CIMG5018a.jpg, 04 Oct 2009.[↩]

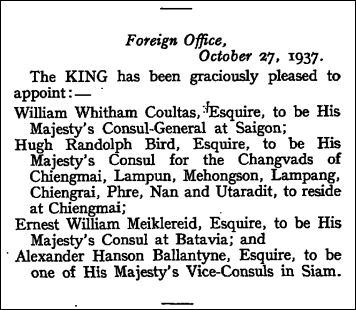

- The London Gazette makes no mention of the appointment of a representative at Ban Kat: for the appointment of Hugh Randolph Bird as Consul for the Changvads:

(London Gazette,(external link) issue 34494, p 1840, 18 Mar 1938).[↩]

(London Gazette,(external link) issue 34494, p 1840, 18 Mar 1938).[↩] - N18°35.855 E98°49.235[↩]

- Some rice had been donated by sympathetic Thais. Some had been received as essentially wage for having helped Thais, typically farmers. Some had been harvested by the soldiers themselves as they traveled[↩]

- Such may have occurred in mid-1943 per SS15, p 140[↩]

- Mosaic of PointAsia views of Ban Kat area, accessed 05 Sep 2008. Annotations by author. Google Earth coverage was substantially inferior in resolution in 2009; in Mar 2012, resolution was satisfactory, but its imagery suffered from a peculiar color washout. The map has not been updated: no relevant features have changed since 2008.[↩]

- 戦没者遺骨収集の記録 ピルマ・インド・タイ [Journal on Collection of Japanese War Dead: Burma, India, Thailand (Tokyo: All Burma Comrades Organization, 1980)], hereinafter “Journal“, p 450. Actual route is not clear; a Google Earth plot along current roads reads 115 km.[↩]

- Interview with Kamroo, 23 Oct 2008[↩]

- 井上 朝義 (えのうえもとよし),彷徨ビルマ戦線(山口県防府市: 大村印刷株式会社,昭和63) [Inoue, Motoyoshi, Wandering on the Burma Front (Hofu: Omura, 1988), p 169[↩]

- ชมธวัช, เชิดชาย, บ้อมูลเส้นทาง เดินทัพทหารญี่ปุ่นในอำเภอบุนยวม สงครามมหาเอเชียบูรพา (สงครามโลกครั้งที2) จดทำโดย พันตำรวจโท [Chomthawat, Cherdchai, Information about Japanese Soldiers Traveling through Amphur Khun Yuam in World War II (self-published, undated)]. Information reported by Interviewee Nos. 2 and 6 (unpaginated).[↩]

- N18°43.87 E98°28.60[↩]

- N18°35.875 E98°49.075[↩]

- Author photo: CIMG3657a.jpg, 09 Sep 2008[↩]

- Author photo: CIMG3658a.jpg, 09 Sep 2008[↩]

- Wat Maan ruin 1.jpg (13:29 11 Jun 2022) emailed by cnxpeter 16:52 17 Jun 2022[↩]

- Wat Maan ruin 4.jpg (13:31 11 Jun 2022) emailed by cnxpeter 16:57 17 Jun 2022[↩]

- N18°36.530 E98°48.770[↩]

- Author photo: CIMG3644a.jpg, 12 Sep 2008[↩]

- N18°35.715 E98°49.235[↩]

- N18°36.685 E98°49.185[↩]

- Author photo: CIMG3654a.jpg, 09 Sep 2008[↩]

- Author photo: CIMG3646a.jpg, 09 Sep 2008[↩]

- Journal, p 453 with annotations by author[↩]

- the name, Muan To, was also applied to Mae Hong Son town from 1917 to 1938[↩]

- N18°36.664 E98°50.862[↩]

- Journal[↩]

- Journal, p 450, annotations by author using Microsoft Publisher in conjunction with translators.[↩]

- Journal, p 422[↩]

- Journal, p 452[↩]

- Handout brochure for memorial service at Ban Kat, unpublished (Chiang Mai, Etou Foundation, Aug 2008); translation by author.[↩]

- “the cultural importance to every Japanese of returning some portion of a dead comrade’s body to his homeland”, as recorded by Max Hastings in Retribution: The Battle for Japan, 1944-45 (New York: Knopf, 2008), p 78, hereinafter “Retribution”[↩]

- see above, section titled 1913-1941 (BE 2456-2484) [↩]

- Journal, pp 419-470.[↩]

- Journal, p 470[↩]

- Journal, p 460 ff[↩]

- Retribution, p 78[↩]

- ข้อมูลทั่วไป (general information on website, www.bankad.ac.th, now a dead link). Per Konishi email of 18 Apr 2012 (Rev 1), by 04 Jul 2012, this school info website had been expanded and historical info was available at History (link now dead). The commissioning date appears to have been 1987 (BE 2530).[↩]

- Per clarification in Konishi email of 18 Apr 2012 (Rev 1).[↩]

- “Details about the Monument Dedicated to Those Left Behind in the Thai-Burma Theatre”: from English language Etou Foundation handout for memorial ceremony on 24 Jul 2008.[↩]

- ibid.[↩]

- Author photo: cimg2236.jpg, 07 Jan 2008[↩]

- See section titled ‘2001 (BE 2544)’ below and footnote[↩]

- From “Etou Foundation Chronological History” in Japanese language at http://ww7.tiki.ne.p-~intuji-ensen.htm, accessed 16 Jul 2010; now unavailable (21 May 2022).[↩]

- Author photo: cimg2252.jpg, 07 Jan 2008[↩]

- Consistent with the Etou website’s History of the Memorial in Japanese (link no longer active).[↩]

- Etou Foundation News (external link) [↩]

- Tigerpix-uap-133.jpg, 24 Jul 2008. Courtesy of ‘Gus’ Gutteridge, Thaigerpics[↩]